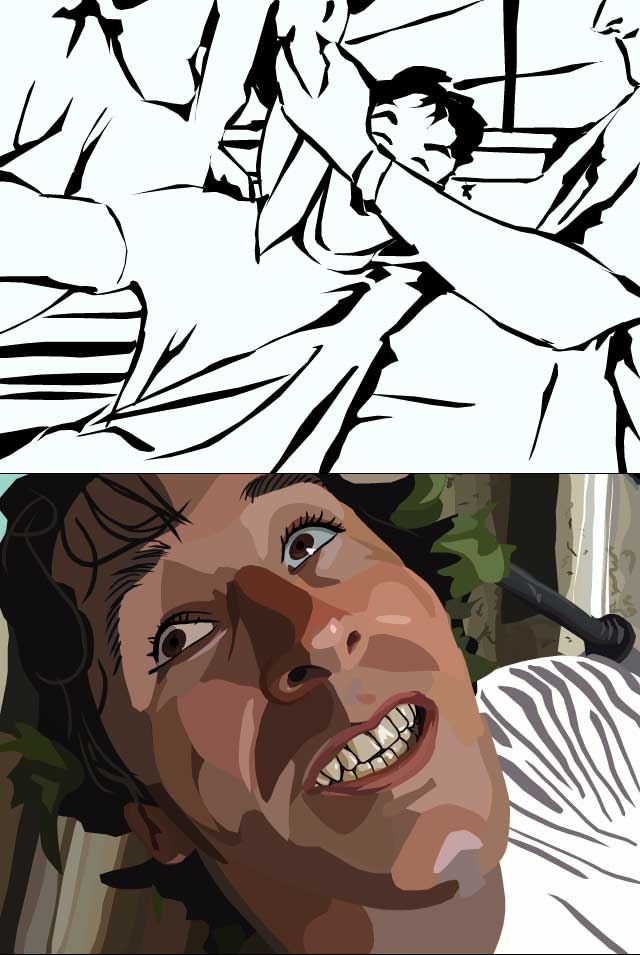

Luc Besson: The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele Blanc-Sec 2010 Luc Besson from The Fifth Element onwards has demonstrated the mastery of the kind of high-resolution imaginative interpretation that I associate with Total Cinema. Here the seamless integration of animatronic and digital pterodactyls and revivified mummies fit well in the Edwardian (Belle Epoque) imagined by Jacques Tardi in his comic books of the same name. But this is not just another example of the brilliant realisation and remediation of the strip form, it is Luc Besson tapping into the ‘steam-punk’ zeitgeist, and like Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s delightful MicMacs of the previous year (and Jeunet’s earlier Amélie (2001), Besson brilliantly evokes a poetic and magical France – here set in the Belle Epoque that marries the whimsical magic of Raymond Peynet, the suspension of disbelief of the fairy tale, with the francophile consciousness of Melies and Feuillade.

Just to recap: the phenomenon of Total Cinema is emerging out of the marriage (or convergence) of computer-generated imagery and filmed live action. This emerging hybrid (film/digital) art form was initially called virtual cinematography (a phrase coined, I think, by John Gaeta, the special effects director on The Matrix series). So virtual cinematography is the beginning of total cinema, and it comprises several technologies that I cover in this blog. To reiterate, these technologies include:

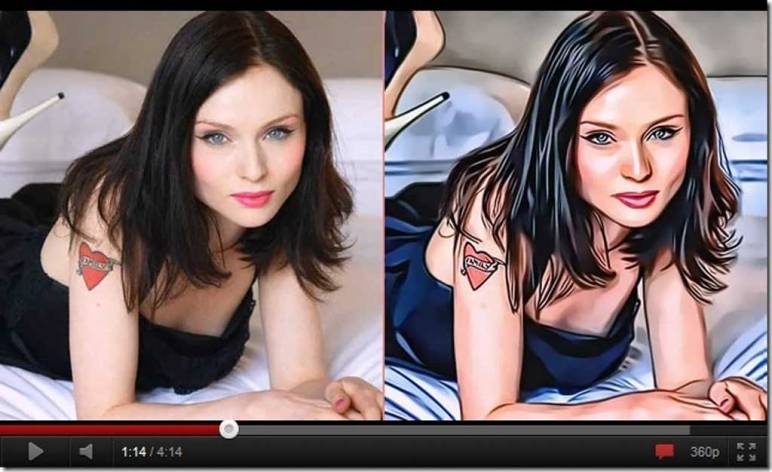

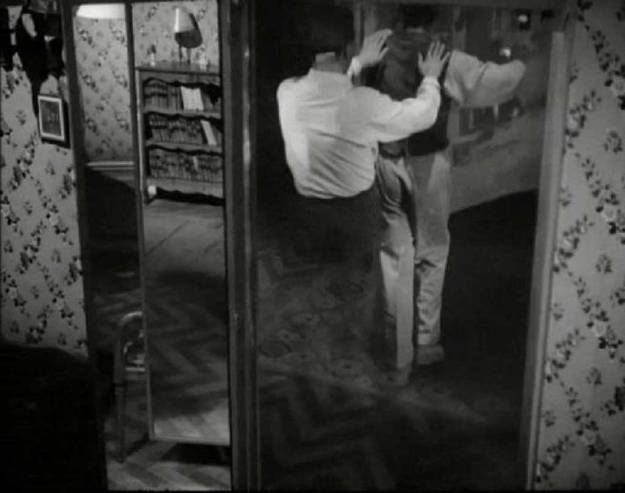

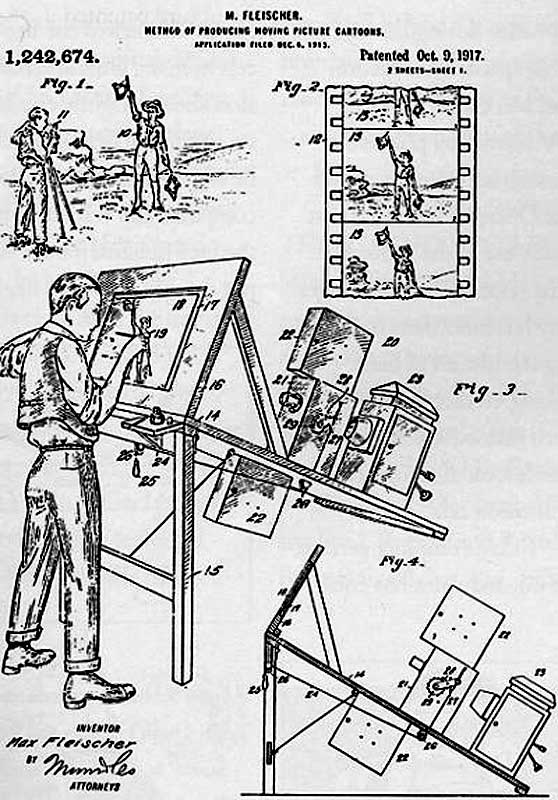

rotoscoping

photo-grammetry

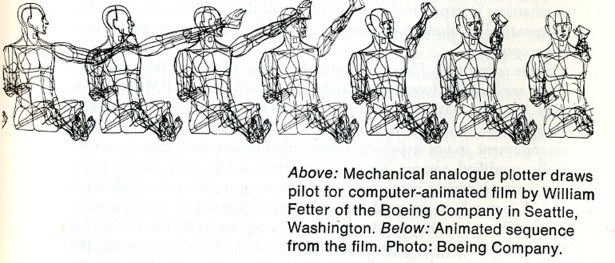

motion capture

compositing

special effects

CGI – computer generated imagery – modelling and animation

crowd simulation software

time-slice video, and bullet-time

augmented reality – virtual reality

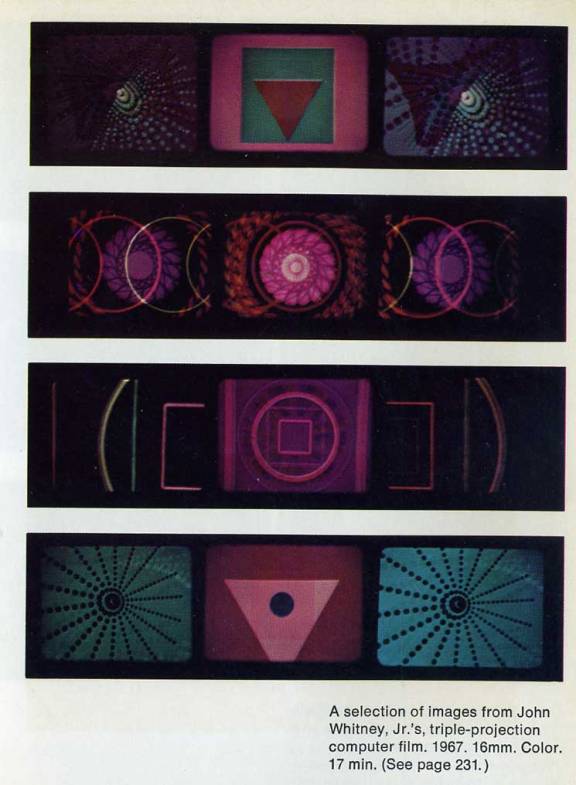

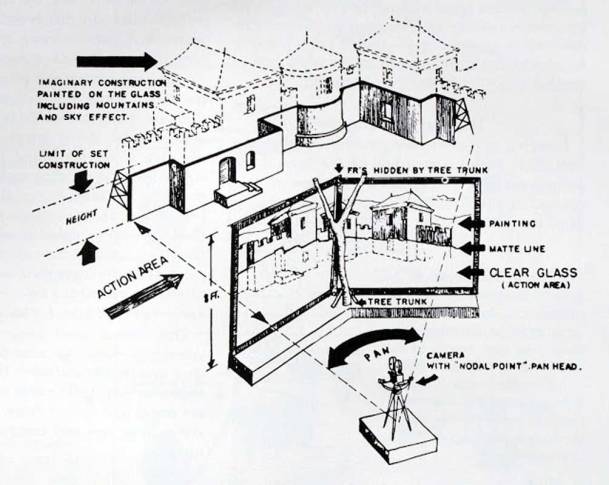

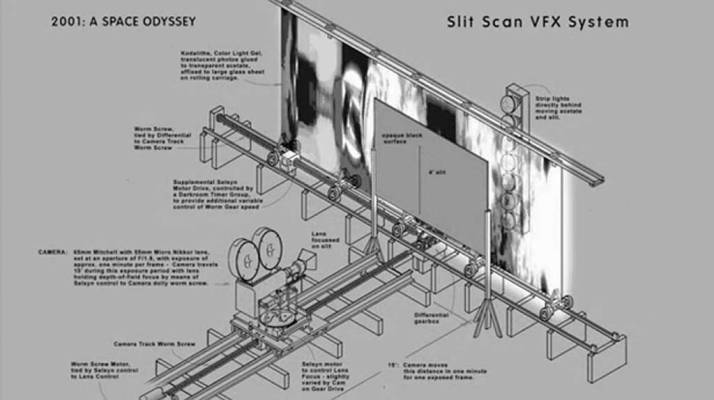

These are the founding technologies of Total Cinema, but the art forms of the 21st century (let’s call them Expanding Cinema – an adaption of the phrase coined by Gene Youngblood in Expanded Cinema his book of 1970, where he surveyed the multitudinous foundations of the new film-related arts emerging from the 1960s counter culture). Expanding Cinema will embrace a far greater range of speculative forms emerging from the digital world, and most especially perhaps the new spaces of augmented/enhanced reality, the world of games, the world of social media, and the contextualisation of film within our culture generally (Secret Cinema, ‘prosumer film-making’ and ventures of this sort).

We are in a melting pot of ideas, of technologies, of art practices and increasing audience empowerment that is changing the way we conceive of films, how we finance films, make films, distribute films, appreciate films, and respond to the cinematic experience. That moving pictures (film, animation and realtime-imagery) will be central to the multi-faceted face of 21st century art, I have no doubt. That these emerging new forms will be immersive, multi-sensory, multi-media, interactive and participative is also most likely. It is also extremely likely that we will never again have a standardised fixed form (as we did during the c90 years dominance of 35mm film technology). We are in a period of what Rosalind Krauss calls the post-medium condition. Expanding Cinema, like the digital computing/software world it now inhabits, is continually evolving. The artist’s palette of the 21st century is itself transforming. It is likely to continue to give us the richest, most accessible, most customisable, most available, continuously evolving, continually expanding cinema…

Peter Greenaway: Tulse Luper Suitcases 2003-04. This is a film-based multi-media project by Greenaway, comprising 4 films – 3 ‘source’ films and one feature-film (DVDs), as well as web-sites, books and CDROMs. “The project has been described by Greenaway as “a personal history of uranium” and the “autobiography of a professional prisoner”. It is structured around 92 suitcases allegedly belonging to Luper, 92 being the atomic number of uranium as well as a number used by Greenaway in the formal structure of his earlier work (most notably The Falls). Each suitcase contains an object “to represent the world”, which advances or comments upon the story in some way, although in many cases the contents are more metaphorical than real.” (wikipedia)

Over the last twenty years, several researchers, fascinated by these emerging forms, have attempted to provide suitable descriptors – Michael Nash in his Vision after Television: Technocultural Convergence, Hypermedia and the New Media Arts field (1996), traces the impact of digital on the ‘traditional’ (analogue) video arts; Peter Greenaway only last year (2014) reiterated his ‘Cinema is Dead, Long Live Cinema‘ mantra:

“Cinema’s death date was 31 September 1983, when the remote-control zapper was introduced to the living room, because now cinema has to be interactive, multi-media art,” and

“Every medium has to be redeveloped, otherwise we would still be looking at cave paintings… New electronic film-making means the potential for expanding the notions of cinema has become very rich indeed.”

(These pronunciations by Greenaway were made at a master class at the Korean Pusan Festival in 2014. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/greenaway-announces-the-death-of-cinema–and-blames-the-remotecontrol-zapper-394546.html)

The diversity of the expanding cinema forms range from viral web videos, to stage illusions/performance, to spectacular films:

Jonas Akerlund and Lady Gaga: Telephone 2010. In this promop-video for her song Telephone, Gaga and Akerlund lean heavily on tropes from Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, orchestrated in a short film story and syncopated by Gaga and Beyonce’s brilliant performance. A ‘pure pop for now people’ production (the descriptor comes from Davie Robinson’s Stiff Records button-badge of c1978), Telephone is a hymn to B movies, Noir film, pulp crime magazines and Captain America pop art. Its great!

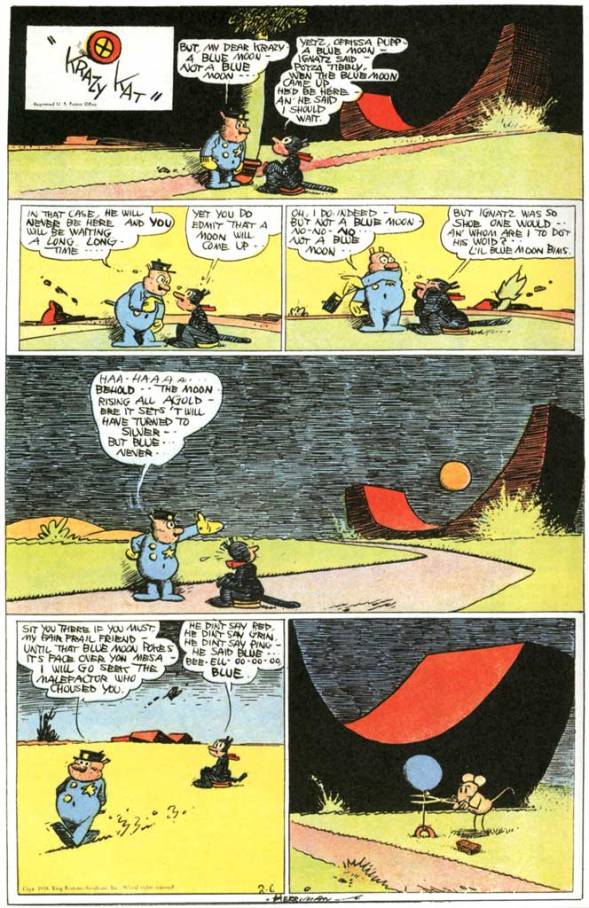

Zack Snyder: Watchmen 2009. Another brilliant remediation of the comic-graphic novel form. As digital imaging technologies, CGI, and special effects arts grew to full maturity in the first decade of the 21st century, It became possible to do full justice to the new wave of reflective superhero comics from the likes of Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, and Frank Miller. Zack Snyder and Robert Rodriguez had worked together on Miller’s Sin City (2005) – a film that to me was the perfect synthesis of film and CGI for this remediated story. Watchmen explores the synergy in a somewhat less stylised form.

Chris Milk: The Wilderness Downtown 2009. In this multi-window, realtime, customisable package, where the narrative is driven by music, Milk and his Google colleagues create a showpiece ‘interactive movie’ that combines generic components composited in real-time with live Google Earth and Streetview feeds. Very powerful – because it is customisable to the individual user/viewer.

Improv Everywhere/Chad Nicholson: Frozen Grand Central 2007. Live participatory, immersive performance – like this and other events staged by from Improv Everywhere (see also Human Mirror 2001) demonstrate another strand of the various media-art experiments intertwining in Expanding Cinema.

Will-I-Am and Jesse Dylan: Yes We Can! 2008. This video went viral in 2008. It was composed by Will-I-am and Jesse Dylan (son of famous Bob), and is comprised of mostly monochrome clips and stills and audio quotes from the Barack Obama’s Presidential campaign of that year. Going viral means that it was recommended by burgeoning links through social media, quickly reaching over 22 million recipients. It was videos like this that awoke marketeers to the promotional potential of the viral, self-recommending nature of media artefacts in the social media matrix.

Musion: Eyeliner projection illusions 2009. Recreating stage presence by using h-tech versions of the 19th century Pepper’s Ghost illusion, Musion added another tool to the rapidly extending vocabulary of multi-media staging and lighting.

Marshmallow Laser Feast: realtime-projection mapping 2012. In this short promo for Sony Playstation, Marshmallow – a team of artists and developers – create what used to be called ‘post-production fx’ in realtime, using clever projection-mapping, performance and digital smoke and mirrors. Phenomenal!

So this is a brief summary of the territory that 2014 film students will be entering. That it is a territory much dreamed about by experimental artists for the last 200 years (see Richard Wagner’s Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft of 1849), and envisioned in many different (analogue) forms by the Modernist avant garde (by El Lissitszky, Rodchenko, Kurt Schwitters, Lazlo Moholy Nagy etc etc), will not deter contemporary students from making their own explorations and innovations in this fantastically rich media palette.