Preface: This talk is intended merely to introduce you to the context of film developments – in both theory and practice – that dominated the 20th century. It is not a detailed history of film. Rather it is an overview of the main developments in film and film theory, contextualised with the relevant aesthetic, technological and cultural histories that frame these developments. We expect you to use these talks and the accompanying pdf (for a copy, mail me at bobcotton@mac.com) as a tool to explore these films more thoroughly in your own time.

From Surrealism to New Wave

The development of Film as a medium of self-expression, narrative story-telling, and communication, is intricately bound up with the broader cultural, technological and historical context in which it exists, so our talk about the period from Surrealism to the Sixties New Wave begins with a brief overview of this context. There are strong links between the two periods (the 1920s and 1930s and the 1960s and 1970s), separated by a world war and thirty-odd years…The ferment of cultural activity that marked the New Wave in the 1960s echoed the Surrealist period in that they both engaged artists, scientists, poets, musicians, writers and film-makers, and both periods bred a generation of artists working in mixed media. New technologies were making the cinematographic arts more accessible to individual artists during both these periods. And war – the recovery from, preparation for, and the actuality of – underpinned both periods.

Surrealism

The surrealists began to coalesce officially in 1924 with the publication of the Surrealist Manifesto by Andre Breton. Surrealism brought together many ideas, tastes and theories, cemented by methods for exploring the unconscious mind (psychology, Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, ethnology, primitive art, Alfred Jarry, Guillaume Apollinaire, Automatic Writing, collage, free-association, the Exquisite Corpse, Marxism, Giorgio de Chirico, DADA, psychic automatism, stream of consciousness, spontaneity, the writings of Marquis de Sade, chance and coincidence, mystical states, the art of the insane, children’s art, free sex and spiritual ecstasy) – these ‘psychic probes’ were the underpinning and the glue of Surrealism.

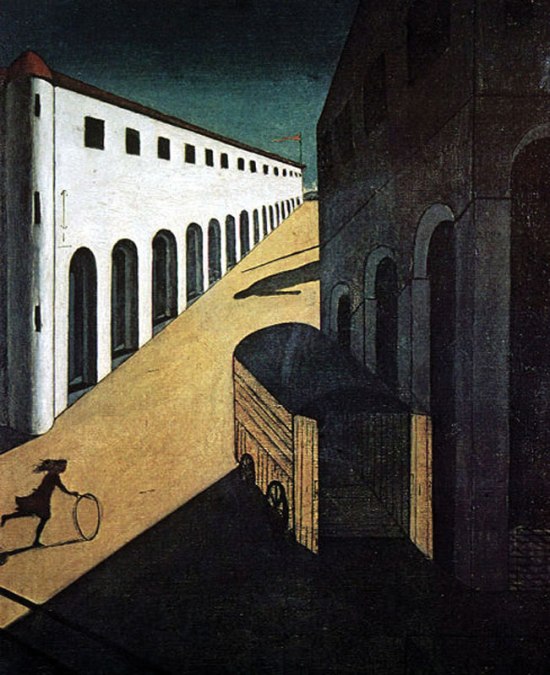

Giorgio de Chirico: Melancholy and Mystery of a Street 1913 De Chirico’s brief adventure with Pittura Metafisca – the series of dream-like, metaphysical paintings using a varitey of perspectives, and perhaps based on childhood experiences in Greece and Turin and Ferrara in Italy – lasted from approximately 1911 to 1918, when he became a ‘classicist’ and spent the rest of his long life (90 years) painting rather staid and unadventurous academic paintings. But this Pittura Metafiscica period was enough to establish him as a landmark artist in Modernism. He was hailed by the Surrealists as a major poetic influence, and his pictures still haunt and beguile. De Chirico’s really seminal work (his paintings from 1913-1919) hinges on this uneasy, semi-somnabulant, juxtaposition of eerie perspectives – often a mix of different (mutually contradicting) vanishing-point perspectives, isometric and axonometric projections – mysterious shadows, a bright ‘moonlight’ , a stasis or frozen moment’. They are powerful dreamscapes, and inspired many Surrealists

Le Surrealist group 1924: Baron, Queneau, Breton, Boiffard, de Chirico, Vitrac, Eluard, Soupault, Desnos, Aragon. Front: Naville, Simone Collinet-Breton, Morise, Marie-Louise Soupault.

Luiz Bunuel, himself a new conscript, introduced Salvador Dali to the Surrealist group after the screening of Le Chien Andalou (1928). In his autobiography, My Last Breath (1982), Bunuel describes his collaboration with Dali on this iconic surrealist film: “When I arrived to spend a few days at Dali’s house in Figueras, I told him about a dream I’d had in which a long tapering cloud sliced the moon in half, like a razor-blade slicing through an eye. Dali immediately told me that he’d seen a hand crawling with ants in a dream he’d had the previous night. ‘And what if we started right there, and made a film?’ he wondered aloud. Despite my hesitation, we soon found ourselves hard at work, and within less than a week we had a script. Our only rule was very simple: no idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted. We had to open all doors to the irrational and keep only those images that surprised us, without trying to explain why.” Luiz Bunuel: My Last Breath 1982 Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali: Le Chien Andalou (1929).

A good general introduction to Surrealism – and other movements in modern art of the 20th century – is Robert Hughes: The Shock of the New – a book and series of television documentaries made in Robert Hughes: The Shock of the New 1980 Episode 5 The Threshold of Liberty (Surrealism)

Man Ray: Noire et Blanche 1926  With an art school training and a background in advertising and drafting, Man Ray learned of the European avant garde in New York from 1911, making friends with Duchamp, and visiting the Alfred Steiglitz Gallery, making collages and holding one-man shows of his work. He followed Duchamp to Europe in 1921, and quickly became a leading member of the Surrealists, while working as a fashion photographer for Paul Poiret. He exhibited work in the first Surrealist Exhibition in 1925, and during the 1920s and 1930s photographed many of the leading Parisian artists. During this time he experimented with photograms (direct-exposure photoprints) he called Ray-o-Graphs. In 1926 he produced a series of photographs of Kiki de Montparnasse (star of Leger’s Ballet Mecanique), several of which feature the African mask in poetic contrast.

Man Ray: Lee Miller (1929)  Max Ernst and Paul Eluard: Les Malheurs des Immortelles (the Misfortunes of the Gods) 1922  Giorgio de Chirico: Nostalgia of the Infinite (1914)  Giorgio de Chirico: Melancholy and Mystery of the Street (1913)  Max Ernst: Une Semaine de Bonte ( A Week of Kindness) 1934

Germaine Dulac: La Souriente Madame Beudet 1922 La Souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) is a short French silent film made in 1922, directed by famed surrealist director Germaine Dulac. It is considered by many to be one of the first truly “feminist” films. It tells the story of an intelligent woman trapped in a loveless marriage. Her husband is used to playing a stupid practical joke. A frequent stunt is one in which he puts an empty revolver to his head and threatens to shoot himself. One day, while the husband is away, she puts bullets in the revolver. However, she is stricken with remorse and tries to retrieve the bullets the next morning. Her husband gets to the revolver first, only this time he points the revolver at her. The bullet misses her, and he thinks she was trying to commit suicide; he embraces her and says “How would I have lived without you?”

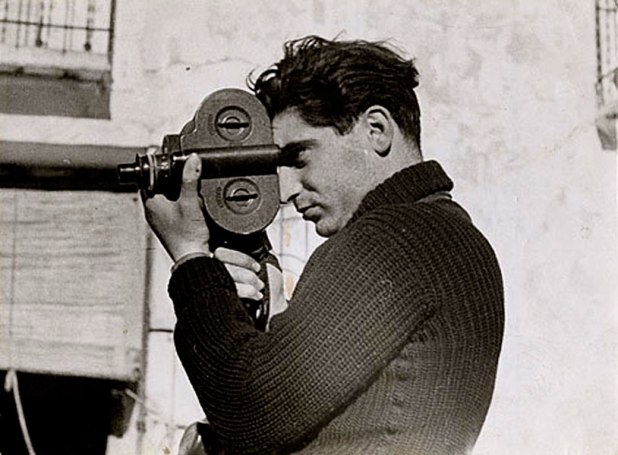

Robert Florey: The Love of Zero 1927 Florey – a Frenchman living in the USA from 1921 – was not ‘officially’ a Surrealist, but his work encapsulates much of the art of the time (surrealism, German expressionism etc), uses montage, and the kind of cubist exploration of cinematography (multiple, superimposed imagery, and in-camera effects) of the kind that that we associate with Walter Ruttman, Dziga Vertov, Fernand Leger, and other avant garde film-makers of the 1920s. The Love of Zero is replete with dozens of technical-aesthetic innovations. Two of the great parallels between the avant garde film revolution of 1920s-1930s and the New Wave of the late 1950s-1960s were this tremendously exciting inter-mixing of media-arts and fine-art; and the impact of new technologies – like the Bell and Howell Filmo 16mm camera (1927), and the Bolex H-16 16mm camera in 1960. The impact of ‘personal’ movie cameras of professional quality, made it possible for film-makers to produce films with minimal budgets – like Florey’s The Love of Zero (1927) – produced for $200!, and the films of Maya Deren (1940s), Curtis Harrington, Kenneth Anger, Stand Brakhage and other avant gardists who created the counter-culture new wave films in the United States in the 1960s.

Robert Florey: The Love of Zero 1927 http://videolog.tv/762071

The idea that a film-maker, working on their own or with a small crew, could work outside the burgeoning Studio System (centred mostly on Hollywood), on work that was experimental, personal, not in hock to remediating plays, novels and existing stories, was new in the 1920s, and began to be revisited in the 1940s-1950s as a precursor of the New Wave (USA), La Nouvelle Vague (France) and Free Cinema (UK).

Early American Avant Garde.

Of course, in the 1920s, the experimentation with cinematography was prolific in America as well as in Europe. The emergence of an avant garde – specifically a tradition of movie-making that was led by non-conventional film-makers, including photographers, artists, dancers, dramaturges…

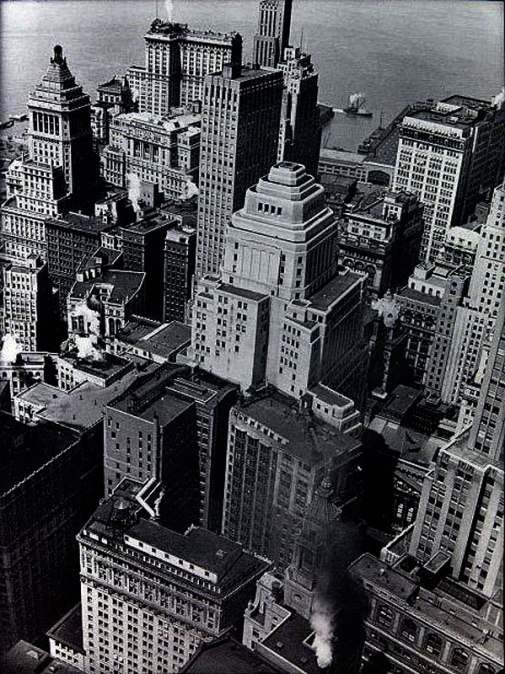

Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand: Manhatta 1921 This is one of the earliest avant garde films. Sheeler was a famous painter and photographer who specialised in documenting America’s industrial landscapes and architecture; Strand a notable modernist photographer, also interested in the aesthetic and abstract possibilities of American architecture.

Amongst the earliest were:  Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand: Manhatta aka New York the Magnificent (1921) Together they made the first in a new genre of films ‘City Symphony Movies’ that were hymns of praise to the modern city, and that characterised avant garde approaches to documentary for a decade or more. Other ‘City Symphonies’ movies included two iconic avant garde films: Walter Ruttman’s Berlin-Symphony of a Great City (1927), and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929). Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler: Manhatta (1921) was the first.

Charles Sheeler: Incantation 1946  Sheeler was part of an often socialist-oriented art movement that celebrated the modern, mechanised culture emerging in the US, while deprecating some of its effects – the oppression of the working classes, the suppression of unions, etc. ~Ben Shahn was probably the foremost of these artists.

Paul Strand: Under the Dark Cloth

Melville Webber and James Sibley Watson: The Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

Melville Webber and James Sibley Watson: The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) “A traveller arrives at the Usher mansion to find that the sibling inhabitants, Roderick and Madeline Usher, are living under a mysterious family curse: Roderick’s senses have become painfully acute, while Madeline has become nearly catatonic. As the visitor’s stay at the mansion continues, the effects of the curse reach their terrifying climax.” (imdb) Webber and Watson’s short film – compressing Poe’s story into 13 minutes – is influenced by German expressionism – esp. Robert Weine’s Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) – and the film matches the storys dream-like, trance-like, nightmare state – the mysterious curse that determines the fate of the siblings.

Melville Webber and James Sibley Watson: The Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

Watson and Webber’s Usher is a veritable catalogue of experimental visual effects – an essay on avant garde film-style, all in 13 minutes. Watson made several other avant garde films: notably Tomatos Another Day (1930), and Lot in Sodom (1933), his collaborator Melville Webber also made Rhythm in Light (1934) – an abstract reflection of what goes on in the mind of a person listening to music…

The Filmo camera series started with the 1923 Filmo 70, beginning a series of models built on the same basic body that was to continued for more than half a century. It was based on Bell & Howell’s brilliantly designed 1917 prototype for a 17.5mm camera intended for amateur use. When invited (along with Victor) into Kodak’s 16mm plans in 1920, the company was quick to see the advantages and immediately set about redesigning the 17.5mm camera for 16mm film. The Filmo 70 was the first spring motor-driven 16mm camera. In 1925 the Eyemo, a hand-held 35mm camera based on the design of the Filmo 70 was offered. It was also spring driven, but could be hand-cranked as well. Bell & Howell introduced the first 16mm turret camera with its Model C in 1927. A beautifully ornate and much more compact 16mm camera, the Filmo 75, marketed primarily as a “watch-thin” ladies’ camera, was offered in 1928, followed in 1931 by a nearly identical counterpart designated as the Filmo Field Camera, offered initially in a plain covering, but also available with the ornate decorations of the Model 75, and in that form indistinguishable from the earlier version except for the nameplate. When Kodak introduced 8mm film in 1932, Bell & Howell was slow to take up the new format, and when it did so, it was not in the form of the Kodak standard. The first 8mm Filmo was offered in 1935 as a single-8 camera, the Filmo 127-A. However, single-8 did not appeal to the market as well as double-8, so the design was modified for double-8 as the 134-A in 1936. Production of Filmos around this body type continued into the 1950s.

Bolex H-16 (1960) and Bell & Howell 16mm Filmo.

The availability of relatively low-cost cine cameras, like Bell & Howell’s Filmo (from 1927), created the technical conditions within which the avant-garde film was possible. This. plus the wave of interest in film, attested to by the growth of film clubs, societies and lecture/talk networks during the 20s and 30s, in which film-makers could meet and talk, in which fans, critics, practitioners, artists found fellow-travellers, collaborators, financiers, and fans created the conditions for a flourishing avant garde, independent industrial (studio) film-making sector.

The Birth of Digital

But before we continue, we must first recognise the birth of what will become (by our 21st century) our dominant, world-embracing media culture – the 1930s marked the very beginnings of digital media – in the landmark development of the ideas for a digital computer.

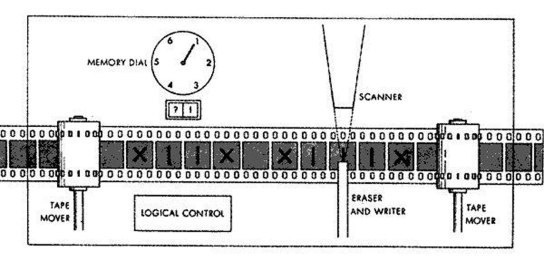

Probably the most significant waypoint in this back-story of where we are now, was the English mathematician Alan Turing’s paper On Computable Numbers published in 1936, where he describes in detail a possible digital computing machine that could theoretically simulate the operation of every other computing machine – this was labelled by others the Turing Machine or Universal Turing Machine. It was the conceptual model for all digital computers, and spurred the invention and development of digital computing during the 1940s.

Alan Turing: diagram of a Turing Machine

Alan Turing: diagram of a Turing Machine

Mike Davey: Turing Machine Simulator

In the 1990s Mike Davey built a working model of a Turing Machine, describing in its actions the processes of writing to, reading from, and erasing from memory, calculation by addition, etc… these simple operations can be used to solve any computable problems.

Why is a film student being introduced to Turing Machines?

Because we live in an age of digital media and software.

Digital Media is Software. All mass media today (films, books, news, records, games, magazines) are digital – and when it comes down to it, they are all strings of zeros and ones – they are all software. The digital computer takes all these strings of data – all these zeros and ones – and uses them to simulate the media they encode, whether it is a picture, a film, a newspaper, a song-recording, a cartoon….

Media becoming Software has several implications, among which are:

* content is mediated by a computer or processor-powered device

* content is infinitely copyable without degradation

* content can be manipulated by code and by the user – it can be interactive

* content can be published online – it can be compressed and reformatted for any digital device

* content can combine several media – multimedia is a concomitant of digital.

And the Turing Machine was the conceptual model for digital computing. Of course the 1940s and 1950s saw the wartime development of digital computers, based on the English mathematician Alan Turing’s 1936 paper in which he described a universal computer – the Turing Machine became the theoretical model for the digital computers developed at Bletchley Park, and Manchester in the UK, and in Germany and the USA in the 1940s.

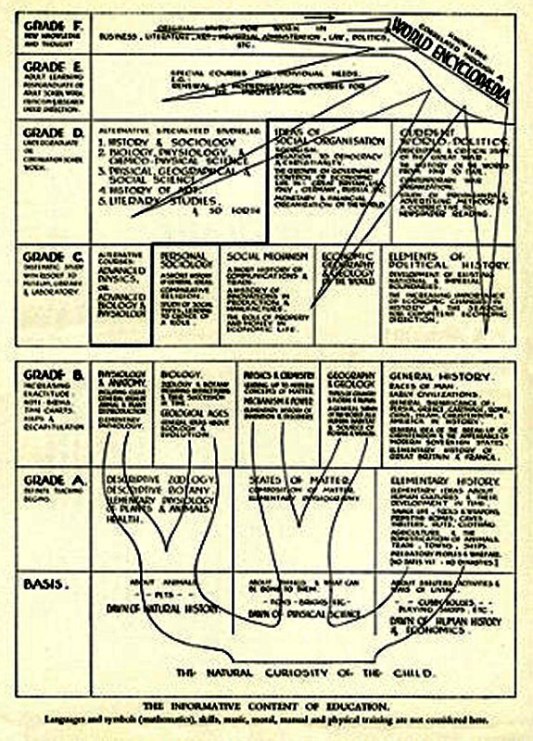

In parallel with these digital developments, the ideas and theories that eventually inspired the Internet and the Web (in the 1960s and 1980s respectively) were published in the 1930s: HG Wells’ World Brain in 1938, and the Belgian Informatics/Librarian Paul Otlet’s Mundunaeum four years earlier.

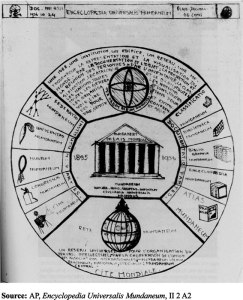

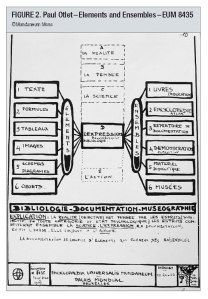

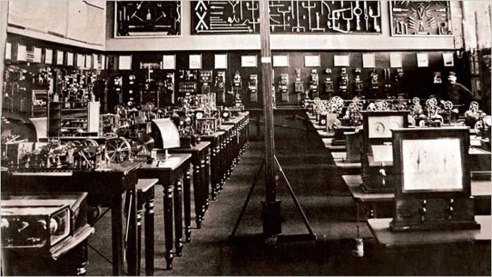

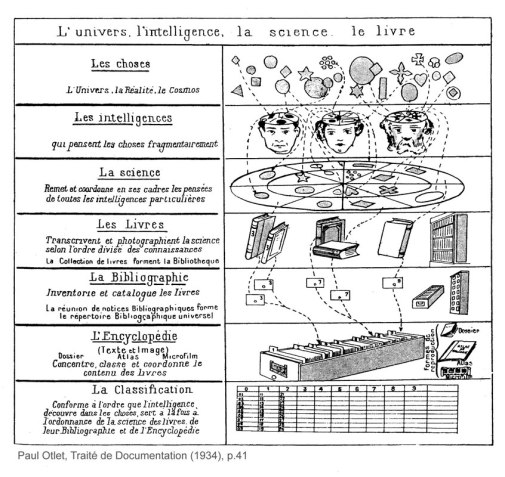

The information-designer and librarian-visionary Paul Otlet’s drawing of the Mundunaeum – the world of information – visualises the role of a central world-library with everyone having access to the information stored within. Of course Otlet is imagining all this in terms of the technological context of his time. The main information technologies in the 1930s were the microfilm, the radio, and the telephone. Emerging was television. Otlet integrates all these into his vision of a global library.

Paul Otlet: The Mundunaeum 1934

H.G. Wells: The World Brain 1938 This essay, The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopedia, was written for the new Encyclopédie Française in 1937, and the next year included in H.G. Wells’ book ‘The World Brain’. In terms of an information-design approach to World problems, it follows Paul Otlet’s revolutionary Traite de Documentation of 1934, and of course sows the seeds of ideas that were to result in Vannevar Bush’s essay As We May Think (1945), J.C.R. Licklider’s paper ‘Galactic Network’ (Online Man-Computer Communication) of 1962, Ted Nelson’s Xanadu hypertext ideas of the mid 1960s onwards, and of course the more recent establishment of the World Wide Web (Berners Lee 1989), and Jimmy Wales’ Wikipedia (2001). It was written as a result of Wells’ determination to do all he could to avert another World War – the threat of which which was looming ominously in the late 1930s. In 1938 the writer and philosopher Herbert George Wells wrote a paper and book suggesting that our classification of knowledge, and the way we encourage access to the accumulated knowledge of mankind are out of date and need to be rethought in the light of then modern communications technologies like microfilm, radio, television, and the telephone. His idea was of a World Brain – a global university/library resource of knowledge available to all. He was dramatising ideas then current among researchers engaged in informatics (information technology), like Paul Otlet, Vannevar Bush and Emmanuel Goldberg.

1938 HG Wells’ World Brain

A member of the socialist Fabian Society, and a supporter of the League of Nations (precursor to the United Nations), Wells was a techno-optimist in his belief that the technology of information science and communications could save the world. (This belief still drives many of us engaged in the new media now – it is the belief that has a basis in the anarcho-syndicalist ideas of the Kropotkin, and more directly the Documentarists of European Information Science (including Otlet). According to a modern iteration of the World Brain, the brilliant Wikipedia: “The essay “The Brain Organization of the Modern World” lays out Wells’ vision for “…a sort of mental clearing house for the mind, a depot where knowledge and ideas are received, sorted, summarized, digested, clarified and compared.” (p. 49) Wells felt that technological advances such as microfilm could be utilized towards this end so that “any student, in any part of the world, will be able to sit with his projector in his own study at his or her convenience to examine any book, any document, in an exact replica.” (p. 54)

A similar view of an automated system for making all of humanity’s knowledge available to all had been proposed a few years earlier by Paul Otlet, one of the founders of information science.

So as you can see, during this mid-20th Century period, most of the essential ingredients of modern digital media: computing and the development of the transistor; Broadcasting; Telecommunications networks; and modern content (music records, film, television, etc) had been developed.

Content-media can be traced to their pre-digital roots in the C19th and early C20th – that is, to the invention of electronic media (Radio from 1900, public broadcasting from the early 1920s, Television from the 1930s) – and of course optical media like the Photograph (1840), and Cinema (1895). By the late 1940s all these ingredients had been reinforced by the publication of the essential theories of Global Information Systems (Otlet and Wells mid 1930s), Computation (1936 Turing), Digital Computers (Zuse 1936, Turing 1941), Computer architecture (1945 von Neumann), Communications Theory (1948 Shannon), Games Theory (1944 Morgenstern and von Neumann), and Cybernetics (1948 Weiner), and of course Vannevar Bush’s ideas about how all this could come together in an electronically-interlinked document-storage system or ‘Memory-extension machine’ he called the Memex (In a 1945 article, ‘As We May Think’).

Why is the classification of knowledge still a really important issue now?

What is microfilm and why was it then seen as the future of information-storage?

Paul Otlet: The Mundunaeum (1934)

New Genres of Movie in the 1930s

Several new genres emerged in the 1930s as older genres were refined. In an era of economic depression and widespread social hardships – soup kitchens were widespread in UK and USA and many Western countries affected by the stock-market crash of 1929. People looked for entertainment that would make them laugh (comedies, cartoons (Betty Boop, Popeye, etc), slapstick (Laurel and Hardy, Marx Brothers), the rom-com screwball comedies – ( Bringing Up Baby ), thrill them (crime (Scarface 1932), , adventure, Westerns, and horror genres, including Dracula and Frankenstein – both 1931), transport them in fantasy (Disney animated features, Wizard of Oz etc) or Religion and the classics ( Ten Commandments, Cleopatra 1934, and dazzle them with beauty and wealth (musicals, Busby Berkely dance spectaculars, etc). Some like the rags-to-riches or poor little rich girl meets working class hero (Sullivan’s Travels 1941, It Happened One Night 1934, My Man Godfrey 1936)

http://www.imdb.com/video/imdb/vi3410886681/

Lazlo Moholy Nagy: Diagram of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce 1947 The Bauhaus master typographer/photographer/painter/industrial designer who replaced Johannes Itten as head of the foundation course at the Bauhaus from 1923. An innovator in form and content, Moholy Nagy had developed his Lightspiel machine in 1922 – and used this to generate his abstract film Black, White Grey. I love this diagrammatic representation of the structure of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, but the best mythopoetic analysis for me is Joseph Campbell’s A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake (1944): Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson annotate and amplify the complex figures in a page-by-page analysis of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake (1939). Their perspective is that of a Jungian mythographer (Campbell) and Poet (Robinson), and the result is an acclaimed work of literary criticism in which the ‘story’ is linearised and the figures of speech and multi-lingual puns teased-out, so the the reader can more easily find their way through a work characterised by Campbell as a product of the collective unconscious. Campbell coins the word ‘monomyth’ in this book.

Just before the War, Joyce finally published the book he had been working on for 27 years, his masterpiece Finnegan’s Wake. This was and is, without a doubt, the most revolutionary book of the 20th century, a mythopoetic ‘novel’ set around a funeral wake, a stream of consciousness composed in multi-lingual puns, with polymathic references, quotes and allusions:  James Joyce started work on his last novel Finnegan’s Wake in 1922, and it was published in 1939. It is his most controversial work, as the book-cum-novel seems to dispense with plot, with logic, and often with language.

Developing his prose style from Ulysses (1922), it is this attempt to render a condition of ‘mythic dreamtime’, through the process of a seeming stream of consciousness, and through a text that contains multi-lingual puns, literary allusions and metaphors, and that is very interesting in terms of the history of media innovation. Several authors of this period experimented with stream of consciousness – the unedited, uninterrupted flow of words tapped as it were from the deep consciousness or sub-conscious mind. Henry Miller successfully interpolated such passages in his otherwise narrative novels (Sexus, (1949) Plexus (1963) etc) , (describing these passages as somehow channelled through him, direct to his fingertips) and the Surrealists experimented with Automatic Writing.

Later in the 1950s both Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs used these techniques in landmark books like Kerouac’s The Subterraneans (1958), and Burroughs Naked Lunch (1959). To enjoy Finnegan’s Wake you either have to make a deep study of it using the various plot-interpretations of scholars like Anthony Burgess or Joseph Campbell (or the several concordances and hypertext examples on the WWW) – or alternatively either read it aloud to yourself, enjoying the tongue-twisting orality of the words, which can envelope you like a richly textured and figured tapestry – or listen to one of the several audio-book versions.  Joseph Campbell’s Skeleton Key to Finnegan’s Wake (1944) gives some idea of the depth and complexity of Joyce’s master work, as does Moholy-Nagy’s schematic above.

– ‘literary criticism in a diagram’ In the 1990s, the Rave theorist Terence McKenna, had this to say about Finnegan’s Wake

In the 1960s, the electronic media guru Herbert Marshall McLuhan was fascinated by Finnegan’s Wake:

“Another theme of the Wake [Finnegans Wake] that helps in the understanding of the paradoxical shift from cliché to archetype is ‘past time are pastimes.’ The dominant technologies of one age become the games and pastimes of a later age. In the 20th century, the number of ‘past times’ that are simultaneously available is so vast as to create cultural anarchy. When all the cultures of the world are simultaneously present, the work of the artist in the elucidation of form takes on new scope and new urgency. Most men are pushed into the artist’s role. The artist cannot dispense with the principle of ‘doubleness’ or ‘interplay’ because this type of hendiadys (double-meaning by linking two-words) dialogue is essential to the very structure of consciousness, awareness, and autonomy.”

Herbert Marshall McLuhan: From Cliché to Archetype (1970) (my emphasis)

How relevant this is now in the 21st Century! When we have access to all the cultures of the world at the click of a mouse, or the swipe of a finger… How is McLuhan’s insight in From Cliche to Archetype relevant to the mediascape now?

Film developments in the 1940s

But lets continue our focus on innovations in film in the 1940s:

Maya Deren: Meshes of the Afternoon n Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), Deren set the tone for the New American Cinema that appeared in the 1950s and especially the 1960s under the rubrics of ‘counter-culture’, and ‘underground’ film-making. With this film, Deren created a new genre – the Trance Film.

Maya Deren and Alexander Hamid: Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

Curtis Harrington: The House of Harrington – documentary reminiscence on movies inc Harrington’s The Fall of the House of Usher 1942 8mm short feature.

Like Deren, Harrington explores waking-dream states, the unconscious, the trance state of consciousness, evoking the surrealist films of Bunuel and Dali (Le Chien Andalou and L’Age D’Or)

1943 Humphrey Jennings: Fires Were Started.

1943 Humphrey Jennings: Fires Were Started.

http://www.previewfilms.com.au/movie-fires-were-started-(1943)-160.htm

This film by Jennings is about the firemen who were fighting fires in the London Blitz – the intense German bombing of London in 1940-1941. It is a ‘documentary’ in that it uses real firemen, not actors, but Jennings uses extensive reconstruction – the re-enactment of actual scenes – thus perpetuating the ethical debate on the Documentary that had started with Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922). Should documentary be a ‘silent witness’ of true life? How far can a documentarist interfere in real-life in order to tell a coherent story? Can a documentarist use reconstructions and re-enactments in order to tell a more ‘truthful’ story? These are the issues discussed since Flaherty used reconstructions to tell the story of the Esquimo he called Nanook, in 1922.

What do you think a ‘pure’ documentary would be? Is Reality TV a documentary? Think of all the documentaries now showing every night on Television – do they use reconstruction?

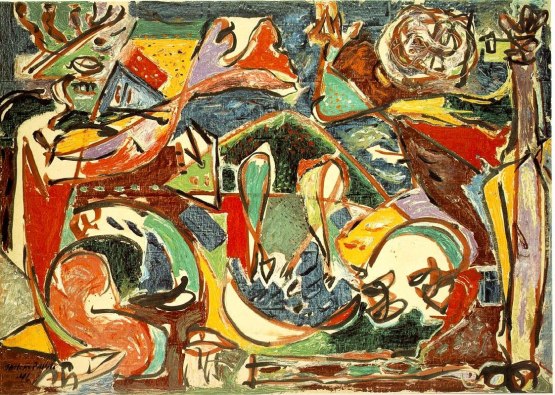

Jackson Pollock: The Key 1946

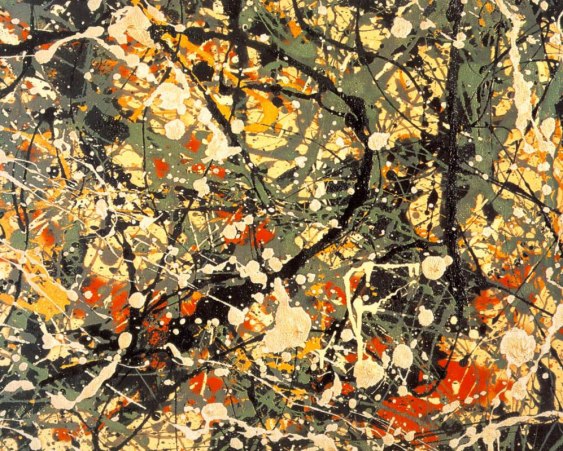

Jackson Pollock: Jungian Unconscious, archetypes and spontaneous gesture – abstract expressionism  Jackson Pollock: The Key 1946 The younger generation of American painters – at first influenced by European artists like Picasso, and the Surrealists, during the 1940s developed a style of work that was later to be called ‘abstract expressionism’ and hailed as the new American art, evangelised by US Government agencies around the world during the early Cold War as examples of American freedom, creativity and self-expression (by implication, an art not possible in the USSR or China). Most representative of the Abstract Expressionists was the painter Jackson Pollock. His early 1940s work is still dominated by an interest in Jungian archetypes and surrealism, but by the end of the decade he is painting vast iconic abstract paintings, dispensing with brush and wall-mounted canvases: Jackson Pollock documentary clip 1951:

Willem de Kooning: Two Women with Still Life 1952

Willem de Kooning: Two Women with Still Life 1952

As you can see, the 1940s was a very interesting period for media-innovations (amplified by the technological accelerator of the second world war!), with coeval developments of free-form bebop jazz, Disney’s Fantasia, abstract expressionism, Meya Deren’s experimental films, digital computers, communications theory, cybernetics, propaganda radio, the emergence of auteur films from Hitchcock, Preston Sturges and others, the protest songs of Woody Guthrie (the beginning of the modern American folk tradition), the emergence of Rock’n’Roll, the Electric Guitar, Long-player vinyl records, Electronic Blues and Rhythm’n’Blues, the development of Crime Noire as a distinctive genre, the mythopoetic films of Jean Cocteau and Marcel Carne, Orson Welles’ iconic Citizen Kane and other films, genius comic heroes (Batman, The Spirit, Captain America), the invention of the Atomic Bomb and Atomic Power, the invention of penicillin, development of blood plasma, helicopters, jet engines, the popularisation of Television, development of integrated RADAR and telecoms systems (British Chain Home System), and much more besides.

Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis et al: Bebop Jazz  Bebop jazz was probably the first iteration of ‘modern jazz’ – it was the first non-dance jazz genre, characterised by improvisation, assymetric phrasing, solo instrumentals, scat singing, and intricate, ‘non-linear’ melodies. Bebop is associated with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Cannionball Adderley and Thelonius Monk. Later in the 1950s and 1960s, variants of Bebop like Cool Jazz, showcased by Chet Baker, Milt Jackson, Stan Getz, Dave Brubeck became very popular. The individual – the solist – takes personal control of the shape of a piece of music, themically linking it to a base tune or melody, but freely improvising around that basic theme. An inspirational model for creative innovation….

My favorite post-Bebop saxophonist is the great John Coltrane: John Coltrane: My Favorite Things (1964) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWG2dsXV5HI  Bebop had its own distinctive ‘cool’ graphics  BlueNote Records with sleeves designed by Reid Miles and photographs by BlueNote co-founder Francis Wolfe, set a distinctive style in graphics, effectively defining the style of jazz albums thereafter.  Frank Sinatra – publicity still 1944 The first mass-media ‘stars’ of musical entertainment (Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, etc) emerged in the mid 1940s as Record producers discovered the synergies possible with US Radio stations, Juke boxes, concert performance, and record sales. In 1944 during a period when he was performing at the NY Paramount, Sinatra was attracting 25,000 fans to a 2000-seater theatre, and earning $4000 a week. (the average wage in US then was less than $1000 a year).

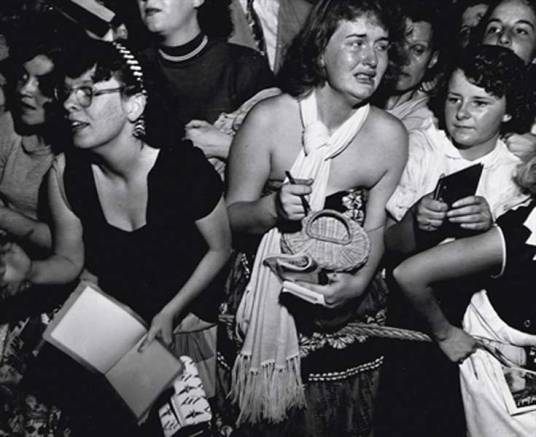

WeeGee: Sinatra Fans riot 1944 Weegee was a street photographer – he took his Speed Graphic camera where the action was, often by eavesdropping on Police radio traffic. Here he captures the latest wave of fan-histeria – this time evoked by the young Frank Sinatra. Earlier iterations of fan worship causing mass histeria had been caused by film stars like Rudolph Valentina and Ramoin Navarro in the 1920s. In the 1950s it would be Elvis Presley, Johnny Ray (the Nabob of Sob) and Bill Hailey (Rock’n’Roll). In the 1960s it was Beatlemania.

Arthur Fellig (WeeGee): Sinatra Fans 1944 (called bobby soxers because of their youth – the word teenager had not been coined yet. Arthur Fellig was famous as a photo-journalist covering NYPD call-outs in the 1930s. Later he collaborated with Stanley Kubrick on short films.

WeeGee: Autograph hunters c1950 Costume designers and stylists take note: these late 1940s girls will become the fans of the fifties heart-throbs – Bill Hailey, Elvis Presley, James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Johnny Cash, Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra. This is WeeGee’s tears and hankies vision of the fans and all their agony and ecstasy.

Fellig would listen in to police radio transmissions, sometimes travelling with the police to the scene of a murder, thus scooping the first reactions, and photographing the victims bodies. (He was nick-named WeeGee because his prompt arrivals at crime scenes seemed magical – as if he was using a Ouija board to foretell the crimes).

The Atomic Age – post Auschwitz and post-Hiroshima

Mavis Tate MP on Buchenwald Extermination Camp http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3wu5PAtj5Ds

I’m trying to give you a collage of the cultural history of the 1940s and 1950s, decades dominated by World War 2, the apocalyptic dawning of the Atomic Age, the horrors of the Nazi Death Camps, the Nuclear Arms Race, post-war reconstruction (the National Health service, and Social Security in the UK), McCarthyism and rabid anti-communism in the US, and the Cold War. These were the global and generational factors that underpinned our life, art and culture in the decades following WW2. The revelations of the horrors of Nazi extermination camps (1945) and the news of the first Atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1946) were to have a global cultural impact. Some of the effects of these atrocities were the emergence of Existentialism, the Anti-War movement, CND, Anti-Fascist movements, in Britain the Angry Young Men (the writers John Osborne, John Wain, Harold Pinter, Arnold Wesker, Colin Wilson, etc. Novels by many of these writers became famous as the kitchen-sink-realism feature films of the 1960s – Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Room at the Top, Billy Liar, The L–Shaped Room, A Taste of Honey, Up the Junction, etc).

George Rodger: Female SS guards bury dead at Bergen Belsen Death Camp 1946

By the end of the war, the American avant garde, kick-started in the mid 1940s by Maya Deren and Curtis Harrington, really got started, spawning talents such as Kenneth Anger, Harry Everett Smith, and others featured in Frank Stauffacher’s Art-Film Club at San Francisco Museum of Art. Hollywood discovered a new source of innovation – B movies developing the Crime Noir genre – films based on the great crime writers of the period – Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Ed McBain. Look at the innovative first-person perspective of Robert Montgomery’s The Lady in the Lake (1947).

While outside US we see Roberto Rosellini’s neo-realist, documentary-style Rome Open City (1945)

1945 -1948 Harry Everett Smith: A Strange Dream and Early Abstractions http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-wYJ51nSXRQ

Harry Everett Smith: A Strange Dream 1948

Smith is a much revered film-maker and innovator in camera-less film – painting and drawing frame-by-frame on the film itself.

SMITH ON SMITH Filmmaker, musicologist, ethnographer, bohemian, and occultist, Harry Smith was one of the most original artists and unusual thinkers in postwar American culture. While living at New York’s Chelsea Hotel during the 1970s, Smith was part of a milieu of underground artists, musicians, and writers, including Allen Ginsberg, Robert Mapplethorpe, Leonard Cohen and Janis Joplin. It was there that he also met the visionary poet and singer Patti Smith, who remained a close friend and colleague until Harry Smith’s passing in 1991.

Jean Cocteau: La Belle et La Bete (1946)

http://www.criterion.com/films/177-beauty-and-the-beast

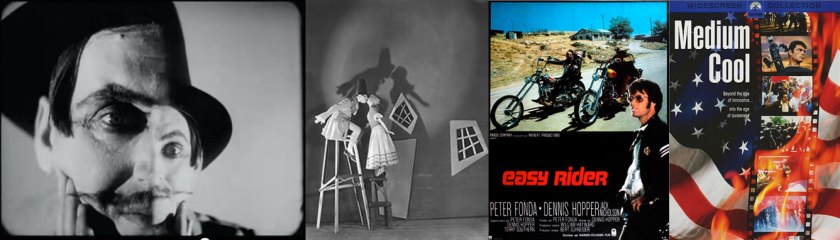

In 1946 Jean Cocteau was in recovery from opium addiction, working in war-torn France, struggling to find film-stock and equipment to shoot this, his filmic-poetic recreation of the traditional fairy-tale The Beauty and the Beast, first published in a book in 1740. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther (1947): “La Belle et la Bete is a “priceless fabric of subtle images,…a fabric of gorgeous visual metaphors, of undulating movements and rhythmic pace, of hypnotic sounds and music, of casually congealing ideas”; according to Crowther, “the dialogue, in French, is spare and simple, with the story largely told in pantomime, and the music of Georges Auric accompanies the dreamy, fitful moods. The settings are likewise expressive, many of the exteriors having been filmed for rare architectural vignettes at Raray, one of the most beautiful palaces and parks in all France. And the costumes, too, by Christian Bérard and Escoffier, are exquisite affairs, glittering and imaginative.” Jean Cocteau: Orphee 1949 http://www.criterion.com/films/610-orpheus One of my favorite films, Orphee retells the story of Orpheus and the Underworld (Orpheus and Eurydice), recast in small French Mediterranean town in the late 1940s, and centred on the Poets Cafe. This is a mythopoetic metaphysical drama, the scene set with the poet Orphee tuning his car radio to catch cryptic messages from the underworld (Cocteau was inspired by the cryptic BBC messages broadcast to Resistance fighters in WW2). Cocteau has no money for optical special effects (requiring expensive laboratory-printing), so he uses simple in-camera effects throughout (slow motion, reverse footage, mirror-imagery etc). 1953 Charles and Ray Eames: A Communications Primer http://laughingsquid.com/a-communications-primer-1953-by-ray-charles-eames/  This is an important development in filmic media – its the first film I know of to combine graphics, animation, voice-over, music and sound-effects, stills and cinematography in a way that we can recognise today as ‘motion graphics’. Charles and Ray Eames were an eminent architect/designer/film-maker team whose work from the mid-1940s onwards made an important contribution to the world of design and communications. This film is also important because it is a remarkable exposition of a fairly complex mathematical paper by the American researcher and mathematician Claude Shannon (then at Bell Telephone Labs)- a paper that was to have great consequences for the design of digital telecommunications systems. Shannon’s central idea is that of the communications channel – from the Source or SENDER of information to the RECEIVER and Interpreter of that information, through a CHANNEL that includes: SENDER (IDEA)>SENT MESSAGE>CHANNEL>RECEIVED MESSAGE>RECEIVED IDEA Shannon proved that there are issues of of semantic encoding and decoding at the SENT MESSAGE and RECEIVED MESSAGE stages (how well the original idea is encoded into a MESSAGE and finally decoded into the RECEIVED IDEA), and also that the CHANNEL itself is prone to distortion due to technical and physical NOISE (like the poor shading in this diagram below):  Shannon’s Theory had been published in 1949, so the Eames’ film was the first attempt to explain and illustrate a theory then only four years old. But the Eames’ do not only rely on abstractions (clear animation and diagrams) to illustrate Shannon’s ideas – they also poetically interpret the ideas (using metaphor and analogy, contextual imagery, music and sound effects). Francois Truffaut: A Certain Tendency in French Cinema (Cahiers du Cinema, 1954) “‘A certain tendency in French cinema’ was the title of the article in the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, in July 1954, in which Truffaut proposed what he called ‘la politique des auteurs’. The article was a polemical attack on the current state of French cinema, written by a young man anxious to start his own film career, and opposed by wehat he took to be the orthodoxy of his native film industry. This feeling was shared by other writers on the magazine whose enthusiasm, knowledge and ambition led them to argue that what they valued most in cinema, especially American cinema, was the product of a unified and organising vision. The vision embodied in the films was, they argued, that of its author, or auteur, the director. The implication of their critical practice was that some individuals, exemplified by Alfred Hitchcock, could transcend the constraints of the industrial practices of Hollywood and make films which explored recurrent pre-occupations in distinctive ways. “… Andrew Sarris, an American film critic and translator of Cahiers, translated la politique des auteurs as ‘auteur theory’. Sarris had his own polemical purposes: he wanted to argue that films produced within an industrial system could have artistic qualities that were conventionally accorded to films from Europe.” Philip Simpson: Authorship in Critical Dictionary of Film and Television Theory (ed E Pearson and P Simpson Routledge 2001) Auteur-Structuralism The Truffaut/Sarris early iteration of ‘Auteur Theory’ hardly deserved the title of ‘theory’. Truffaut’s article was a polemical comment. Sarris did not ground his approach in any explicit theory of how ‘texts’ (films, books etc) were understood. Neither did he describe a methodology; nor take into account how films were shaped by genre, by the marketplace, by the studio system, etc. These ‘structural’ aspects of film production were side-lined by an over-emphasis on the role of the director/auteur. But by the latter 1960s, two works appeared which developed the notion of authorship more widely: Geoffrey Newell-Smith’s Visconti (1967), and Peter Wollen’s series of articles: Signs and Meanings in the Cinema (1966-72). Wollen suggests that we shouldn’t use Art Cinema models as the basis of a critique of Hollywood films.  avant garde auteur model  Studio auteur model  promotional poster for North by NorthWest 1959 Alfred Hitchcock: North by Northwest (trailer) 1959 (Robert Burks DP, Production Design Robert ~Boyle http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HRfmTpmIUwo Hitchcock’s individual film style was exemplified by several characteristics, including: his personal (ex-plot) appearance in many of his films, a story structure based upon The Thirty-Nine Steps cool sense of modernism in composition music by Bernard Herrman Blonde female protagonist The Thirty-Nine Steps meta-plot: innocent man is blamed for a crime he is pursued by villains and by police he is helped (at first reluctantly) by a (blonde) woman he survives several close shaves with the villains he eventually is recognised as innocent and (with the blonde, who has fallen in love with him) he helps capture the villains usually on some famous national monument/building/statue  2007 Martin Scorsese: Key to Reserva – tribute to Hitchcock, Bernard Herrman, Saul Bass etc http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P5nAxzH4OPs How many of Scorcese’s references to Hitchcock films can you detect? Alfred Hitchcock: North by Northwest: Titles Sequence by Saul Bass http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIlqatMQSgI To give you some idea of just how fast the movie-titles-design sector was moving post Saul Bass’ earlier work, In Britain Bernard Lodge (Dr Who), Robert Brownjohn (From Russia with Love) and Maurice Binder (Dr No) were the designers to watch – all three of them setting the styles for the James Bond and Dr Who brand titles for years to come. Maurice Binder: Dr No titles 1962 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYw_vVxw8tg  Robert Brownjohn: From Russia with Love titles 1963 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y952TRNBvDw   1963 Bernard Lodge: Dr Who titles – with Ron Grainer’s electronic score, created by Delia Derbyshire at BBC Radiophonic Workshop: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=75V4ClJZME4 1950 Fred Waller: Cinerama  The increasing popularity of television forced Hollywood to introduce numerous technological innovations in order to compete for audiences. The most successful of these innovations were widescreen and 3-D formats based, ironically, on experiments conducted since the 1890s. The first widescreen process of the 1950s, the triptych Cinerama format used for This Is Cinerama (Merian C Cooper, 1952), was directly inspired by the Polyvision system used in the 1920s, though it added a curved screen to provide a feeling of immersive depth. 20th Century Fox’s CinemaScope anamorphic widescreen format, based on Henri Chretien’s Hypergonar system, soon replaced the more cumbersome Cinerama.   1953 20th Century Fox: Cinemascope In order to fully demonstrate the panoramic potential of the new widescreen formats, a number of biblical epics of the 1920s were remade in widescreen Technicolor, including Ben-Hur: A Tale Of The Christ (William Wyler, 1959; a remake of Fred Niblo’s 1925 original) and Cecil B DeMille’s remake of his own 1923 The Ten Commandments in 1956. (They were dismissed as ‘tits and sand’ films by the industry, for their over-reliance on exoticism.) Since the 1950s, ultra-wide formats have only rarely been utilised for narrative films, relegated instead to novelty attractions such as Imax (Tiger Child by Donald Brittain, 1970). These audience-engulfing, large-screen and multi-screen formats were initially proposed by Stan VanDerBeek in his 1966 manifesto “Culture:Intercom” And Expanded Cinema: A Proposal And Manifesto. There were other quite radical experiments, including Morton Heilig’s Sensorame – a coin-op multi-sensory simulation device:  Morton Heilig: Sensorama 1957 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vSINEBZNCks Stan Vanderbeek radio documentary 2011 https://soundcloud.com/agnes-duchamp/camh-director-bill-arning Vanderbeek had studied at Black Mountain College, where he met the radical architect Richard Buckminster Fuller, the choreographer Merce Cunningham, and the experimentalist composer John Cage. In the early 1960s he built an inflatable studio-theatre – the MovieDrome – at his home at Stony Point NY, worked with ‘Happenings’ creator Allan Kaprow and artist Claes Olderberg, and in the mid-60s developed some early experimental computer-generated films with CG pioneer Ken Knowlton (see Poemfield 1964-67). He is an exemplar of the ‘intermedia’ artist circa early 1960s. ‘Intermedia’ was a label coined by the American Fluxus artist Dick Higgins. In 1995 he produced this retrospective diagram, his Intermedia Chart:  STATEMENT ON INTERMEDIA Art is one of the ways that people communicate. It is difficult for me to imagine a serious person attacking any means of communication per se. Our real enemies are the ones who send us to die in pointless wars or to live lives which are reduced to drudgery, not the people who use other means of communication from those which we find most appropriate to the present situation. When these are attacked, a diversion has been established which only serves the interests of our real enemies. However, due to the spread of mass literacy, to television and the transistor radio, our sensitivities have changed. The very complexity of this impact gives us a taste for simplicity, for an art which is based on the underlying images that an artist has always used to make his point. As with the cubists, we are asking for a new way of looking at things, but more totally, since we are more impatient and more anxious to go to the basic images. This explains the impact of Happenings, event pieces, mixed media films. We do not ask any more to speak magnificently of taking arms against a sea of troubles, we want to see it done. The art which most directly does this is the one which allows this immediacy, with a minimum of distractions. Goodness only knows how the spread of psychedelic means, tastes, and insights will speed up this process. My own conjecture is that it will not change anything, only intensify a trend which is already there. For the last ten years or so, artists have changed their media to suit this situation, to the point where the media have broken down in their traditional forms, and have become merely puristic points of reference. The idea has arisen, as if by spontaneous combustion throughout the entire world, that these points are arbitrary and only useful as critical tools, in saying that such-and-such a work is basically musical, but also poetry. This is the intermedial approach, to emphasize the dialectic between the media. A composer is a dead man unless he composes for all the media and for his world. Does it not stand to reason, therefore, that having discovered the intermedia (which was, perhaps, only possible through approaching them by formal, even abstract means), the central problem is now not only the new formal one of learning to use them, but the new and more social one of what to use them for? Having discovered tools with an immediate impact, for what are we going to use them? If we assume, unlike McLuhan and others who have shed some light on the problem up until now, that there are dangerous forces at work in our world, isn´t it appropriate to ally ourselves against these, and to use what we really care about and love or hate as the new subject matter in our work? Could it be that the central problem of the next ten years or so, for all artists in all possible forms, is going to be less the still further discovery of new media and intermedia, but of the new discovery of ways to use what we care about both appropriately and explicitly? The old adage was never so true as now, that saying a thing is so don´t make it so. Simply talking about Viet Nam or the crisis in our Labor movements is no guarantee against sterility. We must find the ways to say what has to be said in the light of our new means of communicating. For this we will need new rostrums, organizations, criteria, sources of information. There is a great deal for us to do, perhaps more than ever. But we must now take the first steps. Dick Higgins New York August 3, 1966 ————— Published in: Wolf Vostell (ed.): Dé-coll/age (décollage) * 6, Typos Verlag, Frankfurt – Something Else Press, New York, July 1967  Stan Vanderbeek: Science Friction (1959) http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=rvmXDeNGy3s Stan Vanderbeek: Breathdeath 1963 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MMiqsa9VTzc Vanderbeek has been vastly under-rated, as Amid Amidi points out: “ It’s a disservice to label VanDerBeek (1927-1984) merely a filmmaker because he was so much more than that. He was a multimedia artist years before the term even existed. He was constantly getting his hands dirty with new technologies and trying to figure out artistic and educational applications for them. This included creating huge murals via fax machine, projecting film onto steam, and designing interactive multi-screen TV shows. No surprise that VanDerBeek was also a computer animation pioneer who starting experimenting with CGI in 1965. His short films–often surreal, often funny, and always a visual free-for-all–combine animation, collage, cut-out, photography and video, with manic cutting that looks more contemporary than ever. Terry Gilliam has said in interviews that it was VanDerBeek’s cut-out films, and specifically Breathdeath (which will be shown in Ottawa), that inspired his animation style for Monty Python. I’ve personally been influenced by VanDerBeek’s work since I first saw it last year, and I recommend you check him out in Ottawa later this week. The screening will include examples of his analog and CG films, as well as rare film clips of VanDerBeek at work and at play.” Amid Amidi, Toronto International Animation Festival 2009 http://www.cartoonbrew.com/events/stan-vanderbeek-retrospective-in-ottawa-17261.html  Stan Vanderbeek: Breathdeath 1957 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MMiqsa9VTzc  John Stezaker: collage c2005  Stan Vanderbeek: MovieDrome (1963) Lumiere Bros: Photorama at Paris World’s Fair, 1900  Lumiere Bros: Photorama projection-head 1900 Trend towards Immersion Its interesting, and I think indicative of the future of film, that the movies literally began with experiments in immersive-projection, in the tradition of Daguerre’s diorama and panorama and the Lumiere’s 1900 Photorama, and that these experiments are iterated in the evolving story of experimental film: from the Cineorama to Morton Heilig’s Sensorama, from Anaglyptic (red/green) 3D to Hologrammatic theatre, from Gance’s Napolean to the Videowall – from multi-screen and Drive-In to Moviedrome – all these are attempts to evoke this essentially immersive engagement with filmic experience. Recently HD, IMax, BlueRay and 3D are also techno-aesthetic attempts to provide an enhanced immersive experience for the audience. You could argue that Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality, projection-mapping and increasingly large flat-screen technologies also attempt to enlarge the immersive experience. Locative imagery (like the Walking with Dinosaurs A-R app) – by providing the means to superimpose movies on reality (eg dinosaurs superimposed on Isle of Wight beaches) also fosters immersion, as well as reinforcing the sense of living within a hyper-mediated environment. The Counter-Culture Film-maker and Multi-media And the Sixties was a period much given to creative manifestos, stemming from the dawning realisation that contemporary artists had access to tools previously the monopoly of the large corporation mass media. This was generally true throughout the range of mass media – offset litho magazines and journals (Whole Earth Catalog (1968), International Times (1968), OZ magazine 1967 etc), golfball typesetting (IBM Selectric Typewriter1961), low cost cameras (from 1880), cine-cameras for 8mm and 16mm (new models 16mm from 1960, Super8mm electric cine-cameras from 1965 ), portapak video camera(1967), hifi multitrack tape recorders (Ampex Reel-to-Reel multitrack recorders from 1948) etc. With access to professional media tools, and to new networks of art cinema, home movie clubs and film societies, the new avant garde produced new magazines, new types of printed publications (like Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, and Bob Crumb’s Underground Comics), artists could create new hybrid or intermedia forms of art, create loose-knit organisations based upon intermedia (Fluxus 1962, EAT – Experiments in Art and Technology 1966), and promote their work through new forms such as happenings (Alan Kaprow 1959, Jean Tinguely 1960), performance (from DADA and Bauhaus, to inflatables (Moviedrome 1963), and even the new discotheques and emerging club scene (Warhol: the Exploding Plastic Inevitable 1966, Hopkins and Boyd: Underground Freak-Out (UFO) 1966)  Hoppy Hopkins and Joe Boyd: UFO Club 1966 with Live Liquid Lightshow by Marc Boyle and Joan Hills At the same time, musician and artist collaborations, including work by John Cage, Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins, Al Hanson, Yoko Ono, David Tudor etc etc), film and video installations (Vanderbeek, Paik etc), dance and traditional theatre (Living Theater, Peter Brooke at RSC, Le Grande Magic Circus, etc).  Stan Vanderbeek: Culture:Intercom manifesto 1966  Stan Vanderbeek: Culture:Intercom manifesto 1966 Free Cinema and New American Cinema Group Jonas Mekas in a Film Culture editorial in 1960, summarised the impact of the New Wave and the English Free Cinema (the early short films of Anderson and Reisz),.He emphasised their themes closely related to the contemporary generation, the evasion of the polite, slick old plots, the ‘personal’ style, the move towards an increased realism, the documentary aspect, the changing attitude to camera style.In the same article he drew attention to the ‘New American Cinema’ with the same characteristics and strengths.  Second Independent Film Award April 26th 1960, New York. To point out original and unique American contributions to the Cinema FILM CULTURE is awarding its second Independent Film Award to Robert Frank’s and Alfred Leslie’s film Pull My Daisy “(The first Independent Film Award’ (Jan 1959) was given to John Cassavetes film Shadows.) “Looking back through our last year’s film production, we have found a sad and infested landscape, with our official cinema still perpetuating long dead styles, and long dead subjects. Our official cinema is completely out of tune with the times. We however believe that no art in modern times has any value if it is not modern. Only modern art can be creative, and only modern art can be moral. Since it does not place obstacles of cliches of life between man and the immediacy of life. PULL MY DAISY has all these qualities Its modernity and its honesty, its sin cerity, and its humility, its imagination and its humour, its youth, its freshness, and its truth is without comparison in our last year’s pompous cinematic production. In its camera work, it effective ly breaks with the accepted & 1000 years old official rules of slick, polished, Alton & Co cinematographic schmaltz. It breathes an immediacy that the cinema of today vitally needs if it is to be a living and contemporary art.” Jonas Mekas: The Brig (1964) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=382In_SQcDg Mekas was a Lithuanian. Attempting to escape Nazi occupation in 1944, he spent some time in a German prison, eventually reaching America in 1949. He bought his own Bolex 16mm camera and discovered avant garde film, curating his own screenings in galleries in NY. He founded the journal Film Forum in 1958, collaborating with Andy Warhol, Nico, Yoko Ono, Allen Ginsberg, and FLUXUS founder George Maciunas, to create his own personal experimental films. The Brig – his film of the Living Theatre’s dramatisation of Kenneth Brown’s autobiographical play about his imprisonment in a US Marine Corps military prison, is probably Mekas’ best work.  Jonas Mekas: The Brig (1964) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=382In_SQcDg Mekas films the Living Theatre’s production of Kenneth H. Brown’s The Brig – a relentlessly brutal dramatised documentary of life in a US Marine Corps Military prison (the Brig) in the late 1950s. An award winner at Cannes in 1964. Counter culture film-makers were producing movies that could not possibly have been made by the Hollywood studio system. Films like The Brig did the rounds at art-house cinemas, film festivals and Film Clubs at the time. I saw this in the mid Sixties at an all-night BFI screening in Covent Garden. Stan Brakhage: Mothlight 1963 Another great innovator and film-maker during this 1950s-1960s period is Stan Brakhage:  http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XaGh0D2NXCA Brakhage made Mothlight by gluing the wings of dead moths to exposed 35mm film, then sandwiching this with un-exposed film, and contact-printing their patterns, ready for editing and composition. Screening Room film on Stan Brakhage 1973 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l5PGGDCp3VM  Robert Frank and Jack Kerouac: Pull My Daisy 1959 http://vimeo.com/55668342 In many ways Robert Frank was the ‘beat’ photographer. In the mid-1950s he too had gone On the Road, just a Kerouac and his buddies Neal Cassady and Allen Ginsberg had done earlier in the decade. Kerouac’s novel On the Road was written in the early 1950s, but was not published until 1959. So their collaboration on Pull My Daisy was a prescient celebration of young America – the life-styles and patterns, abstract and otherwise, of a generation that, within a few years, would celebrate the new Wave in film, Pop Art and Rock music.   Robert Frank: photographs from The Americans 1958 With the aid of his major artistic influence, the photographer Walker Evans, Frank received his first Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955, then embarked on a two-year journey across America during which he took over 28,000 images. Just 83 made it into the groundbreaking monograph The Americans. RockaBilly, Skiffle and Rock’n’Roll Do-it-Yourself pop music, counter-culture films, and Pop Art. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the popular music scene was radically transformed – first by the growing popularity of Country & Western and Rockabilly, then by do-it-yourself music like Skiffle, then Rock’n’Roll, and the British discovery of Black American Blues music, followed by the iconic blues and rock bands of the Sixties – the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, The Who, Manfred Mann, The Kinks (etc) who reintroduced Black music into the United States.  The early iterations of black music included Fats Domino: The Fat Man (1950), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ICq9lEqj4cI  Jackie Brenston’s and Ike Turner’s Rocket 88 (1951) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gbfnh1oVTk0  Lonnie Donegan Grand Coulee Dam (1957) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Jc2efqj5Js Donegan popularised the work of Woody Guthrie and other American folk singers in the UK in the 1950s… His skiffle technique used home-made instruments inspired by the Jug Bands, black country blues and working-class white folk singers in the 1920s and 1930s. Charting musicians like Donegan and the jazz-band leader Chris Barber were responsible for bringing black musicians and folk-singers to the UK in the 1950s – the early fuel for the British Blues boom of the 1960s..  Maddox Brothers and Rose: Rockin Rollin – Hillbilly to Rockabilly 1937-56 Fuzing Hill-billy-style country and western with rhythm and blues, the Maddox Brothers and Rose explored the fusion of music styles that gave birth to Rock’n’Roll in the early 1950s. Pop Art in UK and USA  Richard Hamilton: Just What is that Makes Todays Homes So Different, So Appealing? 1956  Eduardo Paolozzi: page from a sketchbook 1956  Roy Lichtenstein: Look Mickey 1961  Roy Lichtenstein: Thats the Way it Should have Begun…1963  Roy Lichtenstein: I Don’t Care… 1962  Robert Rauschenberg: Estate 1963  Robert Rauschenberg: Signs 1970 The Beats, Angry Young Men, and Existentialism  Kerouac: On the Road 1957 The Beat writers and poets – Jack Kerouac, Allan Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Neil Cassady, William Burroughs, Lawrence Ferlinghetti (etc) were working for a decade or so before the publication of Kerouac’s On the Road in 1957. The Beat view of life (anti-capitalist, bohemian, poetic, mystical) chimed with teen-rebel movie stars like James Dean (Rebel Without a Cause Nicholas Ray 1955), Marlon Brando (The Wild Ones, Lazlo Benedikt 1953) and Montgomery Clift (The Misfits, John Huston 1961) The New Wave Jules Dassin: Rififi 1955 In Europe, one of the directors blacklisted by the anti-communist House Committee on Un-American Activities and its chair Joseph McCarthy, had moved to France and eventually overcoming considerable opposition from the CIA and US Government, made his most famous film Rififi in 1955. Jules Dassin: Rififi (1955) http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xlvomt_1955-du-rififi-chez-les-hommes-aka-rififi-jules-dassin_shortfilms Jules Dassin Rififi 1955 (production designer Alexandre Trauner – Les Enfants du Paradis 1945) – for Marcel Carne) Truffaut called this ‘Out of the worst crime novel I ever read, Dassin has made the best crime movie I ever saw’ and “Everything in Le Rififi is intelligent: screenplay, dialogue, sets, music, choice of actors. Jean Servais, Robert Manuel, and Jules Dassin are perfect.”  Godard, Belmondo and Seberg during the making of A Bout de Souffle (1960) A Bout de Souffle: Godard 1960 (Breathless or ‘end of breath’) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w2hDR_e1o1M 1965 Godard: Alphaville – Lemmy Caution (played by Eddie Constantine) from the series of Lemmy Caution films based on Peter Chaney’s fictional character) WeeGee: Naked City (1945) Diane Arbus Robert Frank: The Americans (1959) “There is one thing a photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment.” Herbert Marshall McLuhan: Understanding Media 1963  McLuhan’s primary ‘message’ is that the development of media technologies has had a greater social effect than the content of media. Thus ‘The Medium is the Message’. He also argued that electronic media (radio, television, telecoms etc) would collapse spatial and temporal distances between people, thus creating a ‘global village’. Furthermore electronic media (because they are lower definition – he was talking about analogue television like the NTSC and PAL TV standards) encouraged passive or cognitive audience participation – the audience had to work to complete the messages carried by the media. McLuhan called electronic media ‘cool media’ and high-resolution media ‘hot media’. 1957-1963 SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) Dewline Early Warning System – After a decade-long development, SAGE, the first nation-wide integrated computer-radar-telecoms network, was completed in 1963. Modelled on the WW2 British Chain Home System (which integrated telcoms, and RADAR with Operations Centres in SE England, SAGE introduced computers to deal with the processing of potentially hundreds of simultaneous incursions into US air-space. The prototype for SAGE, the Cape Cod System, completed in 1953, was a proof-of-concept exrecise, demonstrating that the interlinking of RADAR stations, air-RADAR, Air-bases, telecommunications networks and Radio was viable. The Cape Cod System verified that the new core-based machine was fast enough for use in SAGE, and an industrial effort was started in order to mass-produce the AN/FSQ-7 (Whirlwind2) computers for this role. RCA was a front-runner, but IBM was eventually selected instead. They started production in 1957, along with a massive construction project to build the buildings, power and communications network needed to feed the SAGE systems with data. map of SAGE coverage in USA  video of SAGE http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06drBN8nlWg  SAGE integrated radar-computer-telecoms network completed 1963  The genesis of Dr Strangelove Like SAGE, Kubrick’s idea for a nuclear movie – a movie about the weird cold-war policy of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) had been in gestation for a decade or so. Fascinated by the fact that, without any public debate at all, the US ‘military-industrial complex’ (Eisenhower’s expression) had constructed a system designed to semi-automatically respond to a nuclear threat or invasion (by bombers, not missiles in those days), with massive reprisals (a nuclear counter-attack). The system was so complex and so prone to accident, coup, or the kind of psychotic malfunction envisaged in Dr Strangelove, that is was a miracle our generation survived. In America, such was a rabid anti-communism of the post-war years, that any public debate on the logic, sanity, or morality of MAD was simply not possible. Kubrick had studies everything he could get hold of concerning the nuclear stand-off, a subject replete with ominous Orwellian terms like ‘overkill’, megadeaths, escalation, zero-sum, pre-emptive strikes, games.. Kubrick read Jaynes Military Aircraft, airforce manuals and magazines, technical data on hydrogen bomb developments, anything he could get hold of. In London he came across a pulp novel by Peter George (an ex-RAF pilot), called Red Alert and began to work with George on a screenplay. But the book was too earnest and melodramatic for Kubrick: “My idea of doing it as a nightmare comedy came when I was trying to work on it. I found that in putting the meat on the bones, and to imagine the scenes fully, one had to keep leaving things out of it which were either absurd or paradoxical, in order to keep it from being funny, and these things seemed to be very real. Then I decided that the perfect tone to adopt for the film would be what I now call nightmare comedy, because it most truthfully represents the picture.” Kubrick, quoted in Lee Hill: A Grand Guy – the Art and Life of Terry Southern 2001, p112 Kubrick calls in Terry Southern, the hipster comic writer of Flash and Filigree, The Magic Christian and Red Dirt Marijuana and Other Stories. 1963 Kubrick/Pablo Ferro: Dr Strangelove film trailer http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gXY3kuDvSU Stanley Kubrick and Ken Adam: Pentagon War Room from Kubrick: Dr Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1963) John Berger: The Success and Failure of Picasso 1965   John Berger: Ways of Seeing (1972) http://vimeo.com/51354092 Like Jean Luc Godard, Berger was a Marxist critic. He made this BAFTA-winning documentary in 1972. In this book and documentary, Berger questions the class and gender assumptions behind traditional oil painting and modern advertising. Berger is essential reading for those engaged in the visual arts. New Journalism: Tom Wolfe to Hunter S. Thompson Ken Kesey New Wave: Easy Riders and Raging Bulls by Peter Biskind (Peter Biskind, looking back on the 1970s….) “When all was said and done, these directors (Peter Bogdanovich, Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, Dennis Hopper, Arthur Penn, John Cassavetes, John Boorman, Peter Yates..etc…) created a body of work that included…The Last Detail, Nashville, Faces, Shampoo, A Clockwork Orange, Reds, Paper Moon, The Exorcist, Godfather part 2, Mean Streets, Badlands, The Conversation, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Apocalypse Now, Jaws, Cabaret, Klute, Carnal Knowledge, American Graffiti, Days of Heaven, Blue Collar, All that Jazz, Annie Hall, Manhattan, Carrie, All the President’s Men, Coming Home and Star Wars..” (you should also include MASH, Bonnie and Clyde, Barry Lyndon, Rosemary’s Baby, The Wild Bunch, Midnight Cowboy, 5 Easy Pieces, The French Connection, McCabe and Mrs Miller, The Last Picture Show, Easy Rider, Performance, Insignificance, The Man Who Fell to Earth, Deliverance, Point Blank, Women in Love, Don’t Look Now, Chinatown, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Good, the Bad and the ugly, Once upon a time in the West, Once upon a time in America, etc…) “The new power of directors was legitimised by its own ideology, ‘auteurism’. The auteur theory was an invention of French critics who maintained that directors are to movies what poets are to poems. The leading American proponent of the auteur theory was Andrew Sarris, who wrote for the Village Voice, and used this pulpit to promote the then novel idea that the director is the sole author of his work, regardless of whatever contribution the writers, producers and actors may make.” Biskind: Easy Riders and Raging Bulls 1998