Jean Cocteau, following the surrealists, really epitomised the magical realism or cine-poetic approach to film-making. Not many poets had tried their hand at movie-making before Cocteau, especially not poets particularly fascinated by the mytho-poetic dimensions of fable, fairy story and myth. Cocteau’s two signature post-WW2 movies – La Belle at La Bete (1946), and Orphee (1949) are absolutely must-see films in this refined genre – pioneer films that still stand pretty much on their own, despite the spate of fantasy and magic-realism films that have emerged coevally with modern CGI and digital sfx.

As a reminder of Cocteau’s ingenuity during this post-war period, when film stock was hard to come by, finance was difficult, Cocteau was 57 years old in 1946 when he made La Belle et la Bete, had recently recovered from an opium addiction. Cocteau could not afford the kind of expensive optical and special effects that Hollywood took for granted. He had to invent his own ‘effects’ to bring his re-telling of the story of Orpheus and the Underworld to the screen. In-camera effects and simple special effects were his narrative tools.

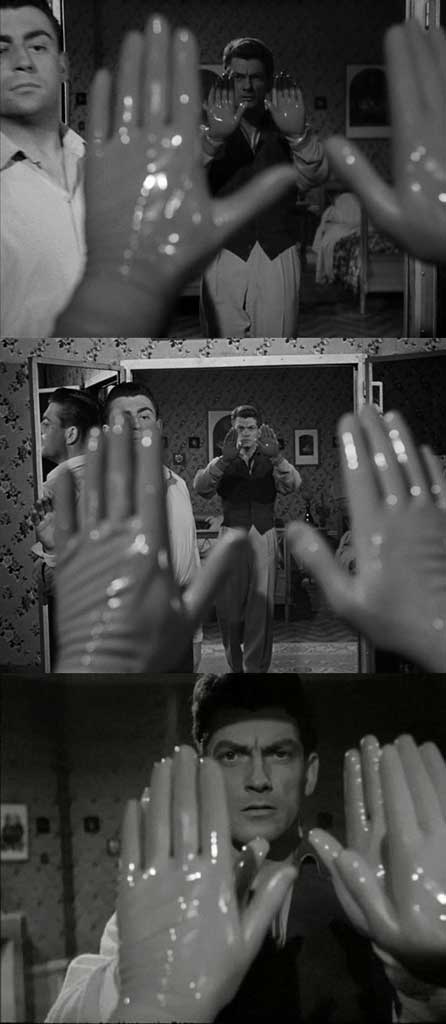

Jean Cocteau: Orphee, 1949. Cocteau, strapped for finance, had to use his ingenuity in making the special effects necessary to illustrate Orphee’s transition from the real to the mythopoetic world of the underground. Cocteau chooses the device of the mirror, clever cutting, and a highly reflective basin of mercury. In this sequence we see Orphee approaching the mirror (or is it a pair of hands approaching Jean Marais, wearing the same rubber gloves? Also in this part of Orphee, we see Cocteau reversing the film so that Orphee’s rubber gloves seem to snap on instantly. These simple tricks are very impressive and disbelief-suspending.

Cocteau was making these movies in the context of a surge of interest in poetry and myth signalled by James Joyce: Finnegan’s Wake (1939), Erwin Panofsky: Studies in Iconology (1939), Joseph Campbell: A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake (1944), Robert Graves: The White Goddess (1948), Joseph Campbell:The Hero With A Thousand Faces (1949). In the wake of the mythic horrors and devastation of the Nazis and World War 2, and the dawn of the Atomic age with its apocalyptic threat, these timeless subjects came to the fore as mankind searched for new meaning as first peace, then a new ‘cold war’ era, dawned.

Although not a member of the ‘official’ Surrealists, Cocteau’s trilogy of films related to the legend of Orpheus: Blood of a Poet ((1931); Orphee (1949), and Testament d’Orphee (1960) fit well within the surrealist’s spectrum of interests (the subconscious, dreams, myths, universal archetypes, magic, chance, automatic writing, etc). Perhaps, like Appollinaire, Cocteau, in his twenties, had been influenced by the fantastic film series of Louis Feuillade (Fantomas (1913), Les Vampires (1915), Judex (1916). None of these films relied on much more special effects than George Melies had at his disposal, it was their dark mystery and hints of the supernatural that the Surrealists admired. Interestingly Georges Franju made a brilliant re-make of Judex in 1963.

Other significant surrealistic films that Cocteau almost certainly would have seen include:

Rene Clair: Entr-Acte 1924

Lotte Reiniger: Die Abenteur des Prinzen Achmed 1926

James Sibley Watson/Melville Webber: The Fall of the House of Usher 1928

Germain Dulac and Antonin Artaud: The Seashell and the Clergyman 1928,

Man Ray: L’Etoile de Mer (1928)

Jean Epstein: The Fall of the House of Usher 1928

Luiz Bunuel/Salvador Dali Un Chien Andalou 1929

Marx Brothers: Animal Crackers 1930

Carl Dreyer: Vampyr 1932

Marx Brothers: Duck Soup 1933

Dave Fleischer: Betty Boop as Snow White 1933

Marx Brothers: A Night at the Opera 1935

Charlie Chaplin: Modern Times 1936

Curtis Harrington: Fall of the House of Usher 1942

Maya Deren/Alexander Hammid: Meshes of the Afternoon 1943

Walt Disney/Salvador Dali: Destino 1945

While this is speculation (on what Cocteau saw), I wanted you to see that Cocteau’s work, though unique, fits within a broader tradition of artists exploring the unconscious, magic, myth and fable, and the absurdity of modern life.

Of course, making serious films in post war France, even with financing from the generous Duc de Noaille was difficult and to optimise his visualisation of the Underworld, Cocteau was forced by circumstance to be inventive with his special effects, resorting to the simplicity of the smoke and mirror ideas of Melies, and using in-camera effects.

Special effects can often be as simple as ‘in-camera’ effects – you know: the iris fade to black/or white, double exposure, running film in reverse, stop-motion, elapsed time, slow motion, rotating camera, inverting camera, using negative as positive, (etc).

Jean Cocteau: Orphee (1949). Heurtebise, Death’s chauffeur, follows Orpheus through the mirror into the Underworld, distance-fogging (under exposure) underlines the illusion.

http://www.criterion.com/films/610-orpheus