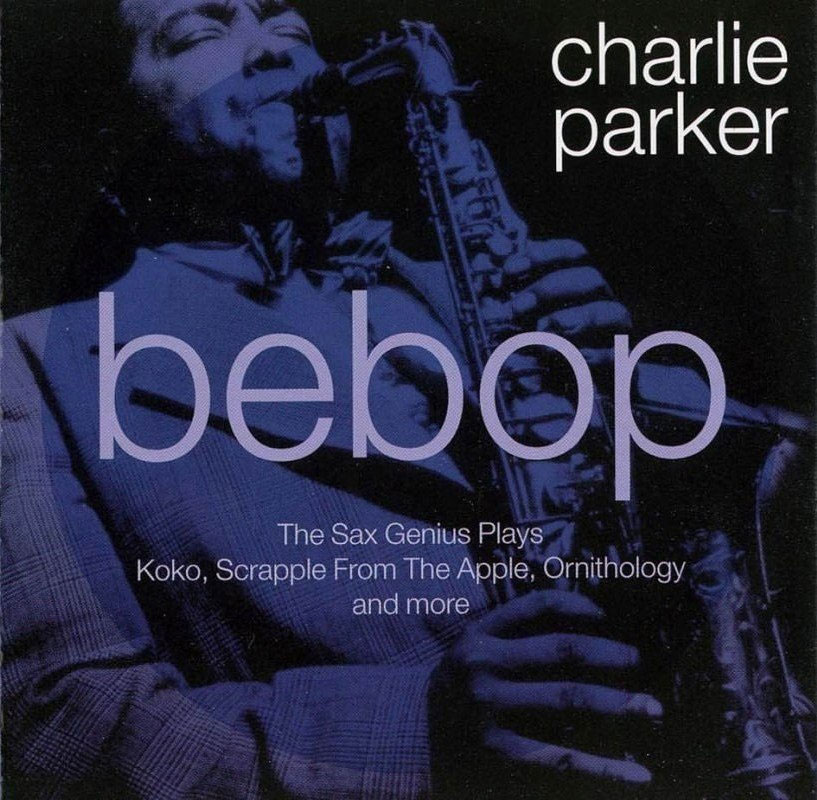

Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis et al: Bebop Jazz  1939 – 1945

Bebop jazz was probably the first iteration of ‘modern jazz’ (though Louis Armstrong had introduced the extended improvised solo in the 1920s) – Bebop was the first non-dance jazz genre, characterised by improvisation, assymetric phrasing, solo instrumentals, scat singing, and intricate, ‘non-linear’ melodies. Bebop is associated with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Cannionball Adderley and Thelonius Monk. Later in the 1950s and 1960s, variants of Bebop like Cool Jazz, showcased by Chet Baker, Milt Jackson, Stan Getz, Dave Brubeck became very popular. The individual – the solist – takes personal control of the shape of a piece of music, themically linking it to a base tune or melody, but freely improvising around that basic theme. An inspirational model for creative innovation…. My favorite post-Bebop saxophonist is the great John Coltrane.

Bebop had its own distinctive ‘cool’ graphics  BlueNote Records with sleeves designed by Reid Miles and photographs by BlueNote co-founder Francis Wolfe, set a distinctive style in graphics, breaking new ground in display typography, hinting at Swiss School breakthroughs, effectively defining the style of jazz albums thereafter.