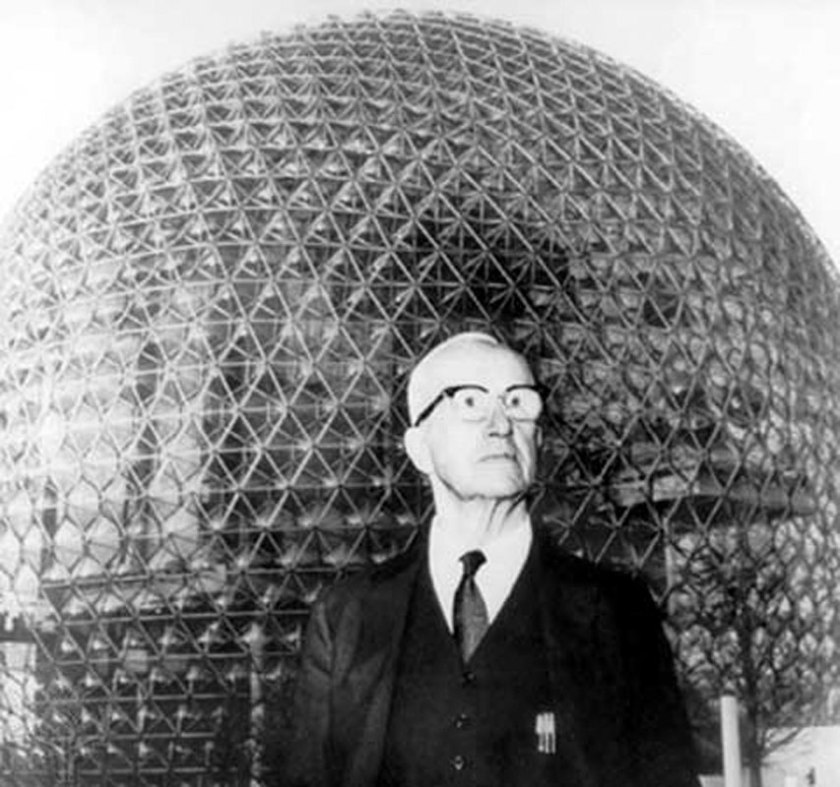

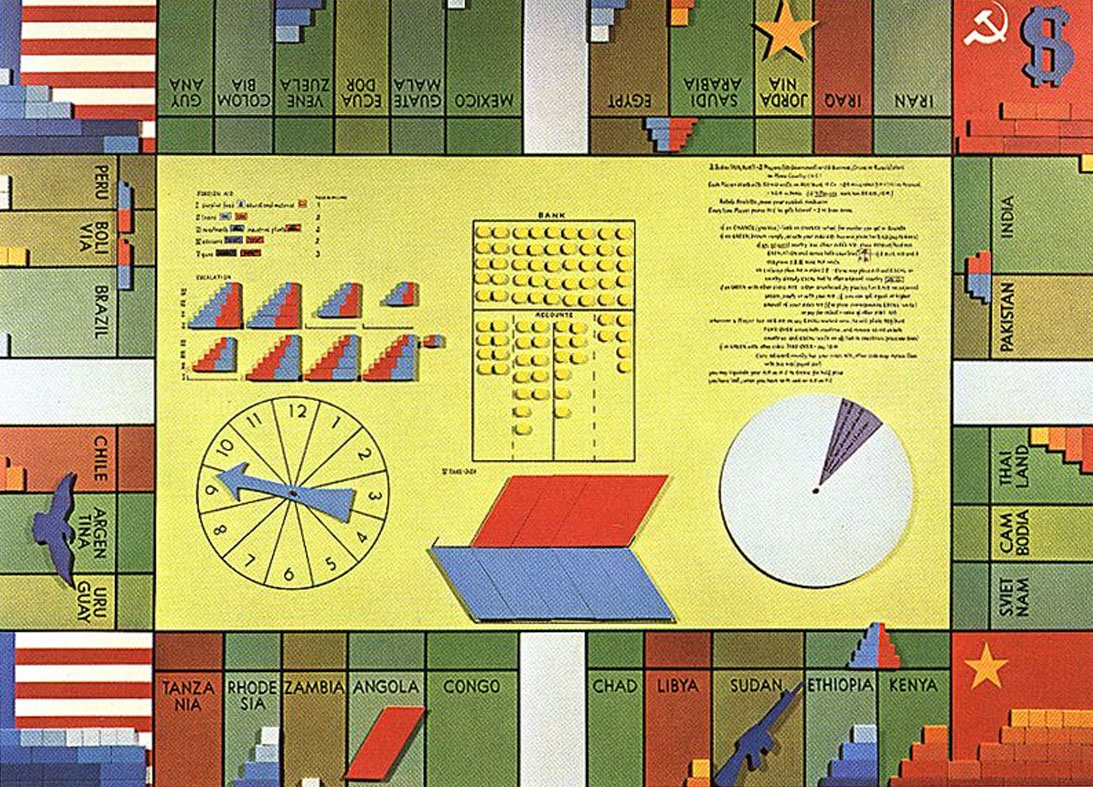

In the early 1960s, working with the English futurist John McHale and the architect Shoji Sadao, Fuller began work on his idea for a World Game with a geodesic Geoscope data-visualisation tool. The geoscope was a 200-foot sphere studded with light bulb-size ‘pixels’ that could display a variety of geo-political, geo-physical, and other data – the World’s resources, World population, pollution, de-forestation, etc. These would be the results of a World Game program – a simulation of the planet and its resources, where design-scientists, engineers, – even politicians – could suggest policies for how to ‘“make the world work for 100% of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone”. These grand ideas were reinforced by Fuller’s books: An Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth‘ and the World Resources Inventory, and by his descriptors: Spaceship Earth, Design-Science, Doing More with Less. Fuller’s idea was that geoscopes would be suspended, using cables and pylons, over every major city on the planet – a constant reminder of our global responsibility – a way for factions to show how they would make the world work for everyone. This vision of a techno-utopia, governed by successful design-science strategies rather than mysticism and political factionalism, was hugely popular in my generation of architects, artists, designers, and ‘alternative-technologists’. His ideas and inventions were celebrated a few years ago in a major retrospective at the Whitney in New York. I was lucky to hear him speak at the new city centre in Milton Keynes in the late 1970s – he spoke for about 3 hours without notes, and captivated everyone. Then he applauded us!