Karel Capek published Rossum’s Universal Robots in 1921, simultaneously inventing the word Robot, and creating a science-fiction tradition in Czechoslovakia. Robot is derived from the Czech Robota – which can mean work you don’t really want to do, or work that is tedious. His play has been performed around the world, and the word Robot was subsequently made really famous by Isaac Asimov in the 1940s (stories collected as I Robot 1950).

In 1938, the BBC’s nascent Television Centre produced a version of RUR (picture below).

Also in 1938, Richard Buckminster Fuller in his book Nine Chains to the Moon, describes a man as:

“A self-balancing, 28-jointed adapter-base biped; an electro-mechanical reduction-plant, integral with segregated stowages of special energy extracts in storage batteries, for subsequent actuation of thousands of hydraulic and pneumatic pumps, with motors attached; 62,000 miles of capillaries; millions of warning signal, railroad and conveyor systems; crushers and cranes (of which the arms are magnificent 23-jointed affairs with self-surfacing and lubricating systems, and a universally distributed telephone system needing no service for 70 years if well managed); the whole, extraordinarily complex mechanism guided with exquisite precision from a turret in which are located telescopic and microscopic self-registering and recording range finders, a spectroscope, et cetera, the turret control being closely allied with an air conditioning intake-and-exhaust, and a main fuel intake.”

1938 BBC Television produce RUR as a tv play

Early 1920s – an early production of the play RUR.

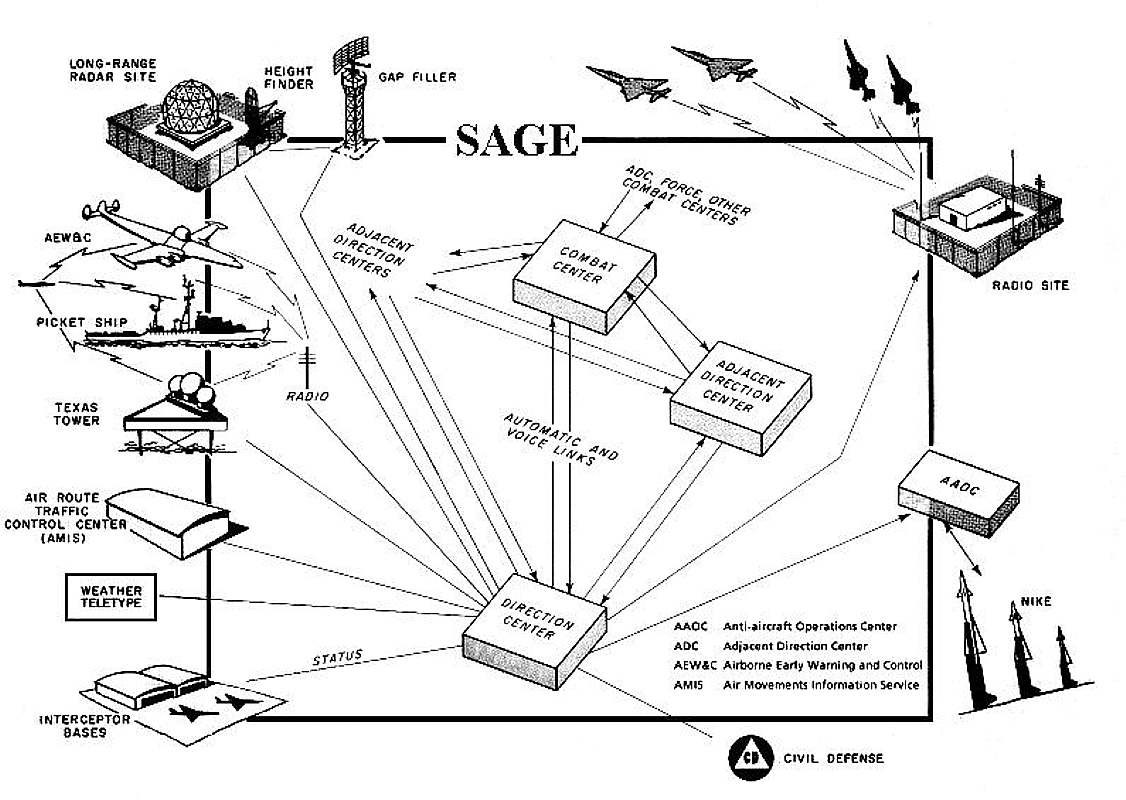

By the 1940s the word Robot was popularised world-wide by the American sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov, who writes a series of books featuring advanced robots including I, Robot, and invents his Three Laws of Robotics. During the period 1950-2000, robots went from fiction to fact, a causal chain perhaps beginning with Grey Walter’s Tortoise autonomous robots in 1949. Coeval with Robotics, the science of artificial intelligence (including machine-vision, machine reasoning, voice-recognition, speech synthesis, Turing-test programming, software agents, etc etc) developed and splintered into a variety of sub-specialisms. From the late 1940s, we have another parallel and overlapping science – that of cybernetics – ‘command and control in man and the machine’ (Weiner 1948). It was the convergence and synergetic outcome of these three disciplines (robotics, AI and cybernetics) that put us on the road to the eventual creation of what Hans Moravec calls an ultra-intelligent machine.

In 2013 alone, 179,000 industrial robots were sold worldwide.